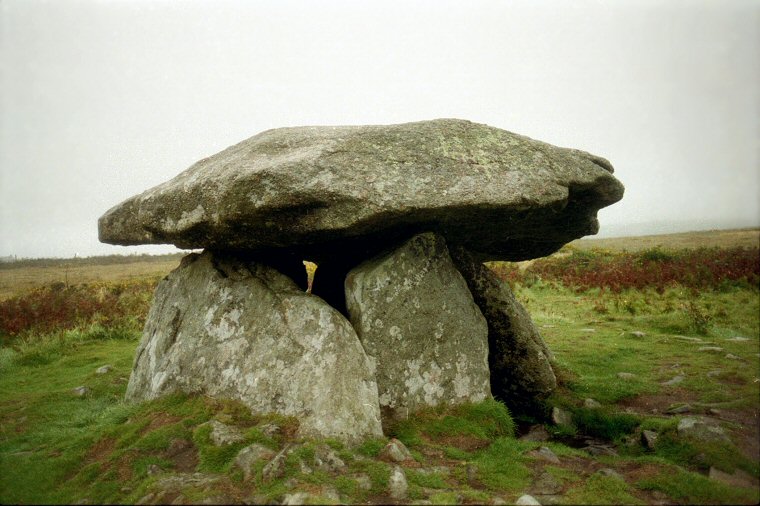

A wet and overcast day at Chun Quoit, September 1997 looking northwest.

The side stones of the chamber consist of four slightly inwards leaning slabs of granite that although they appear to be set out in a rectangle aligned northwest to southeast externally, actually form an almost square inner chamber measuring about 1.9 metres by 1.7 metres internally at ground level. Three of these stones support a roughly circular domed granite capstone over a metre and a half above the ground, the capstone measuring around 3.7 metre wide and about 80cm thick. The slab to the southwest doesn't quite reach the bottom of the capstone, whether this was also so or whether it has slipped inwards over time is not known.

The chamber is set within the remains of a roughly circular cairn of about 10-14 metres diameter that now stands less than a metre high, with most of the loose stones presumably having been cleared away over the centuries. The cairn would never have covered the chamber, perhaps only reaching part way up its sides. It was edged with a revetment or kerb of low stones, most of these are now also lost, however a few still exist along the north-northeastern edge of the cairn (on the right hand edge of the cairn in the photograph above). To the south a single stone stands perpendicular to the cairn edge (in the left foreground above) with a fallen stone nearby, these are not believed to be part of the kerb but have been interpreted as either the remains of a stone cist or more likely as part of an entrance passage through the side of the cairn to give access to the chamber.

Chun Quoit was recorded by the antiquarian William Borlase in the mid 18th century and investigated by one of his descendants, William Copeland Borlase, in the late 19th century (a transcript of his excavation is provided below) and while he discovered some interesting details of the tomb's construction he failed to find any material items beyond a single piece of unspecified flint, the interior of the chamber probably having been previously cleared out by unscrupulous treasure seekers many times in the past.

Chun Quoit can be reached by following a track from the nearby farm, which also takes you past the nearby Chun Castle, a small 3rd/2nd century BC Iron Age hillfort. When visited in late Summer, the fort was completely overgrown with bracken and it was almost impossible to make out any of the circular and rectangular huts that have managed to survive much of the stone being removed for paving the streets of Penzance.

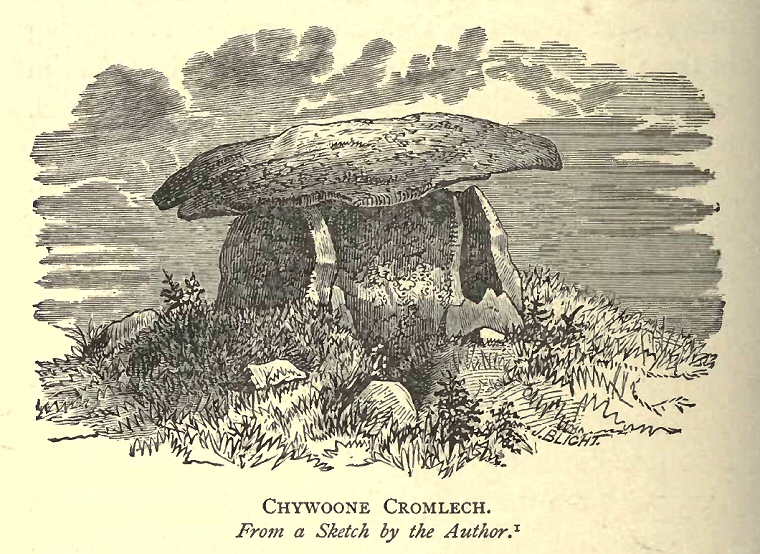

The name 'Chun', or more correctly in Cornish, 'Chûn' or 'Chuûn' and pronounced 'Choone' comes from 'Chy-an-Woone' or 'Chywoone' meaning 'the House on the Downs'.

Date: Neolithic

View looking north-northeast. The slab to the left of the picture doesn't quite reach the capstone.

James Halliwell visited Chun Quoit in the mid 19th century and declared it to be 'the most perfect specimen in the county', this despite also describing it as having 'the appearance of a gigantic mushroom'.

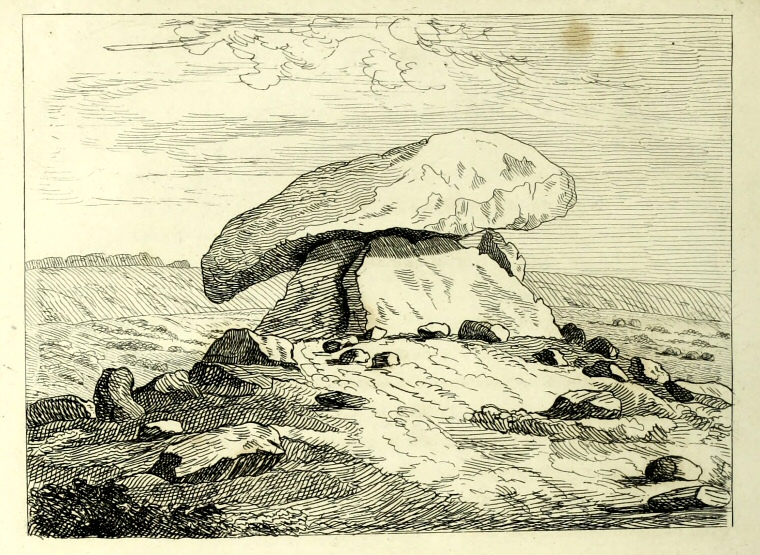

Illustration of Chun Quoit by William Cotton published in 1827.

William Copeland Borlase excavated Chun Quoit, or as he calls it, Chywoone Cromlech in 1871 but found the site overgrown with furze and with very little remaining in the interior of the chamber.

Excavation:

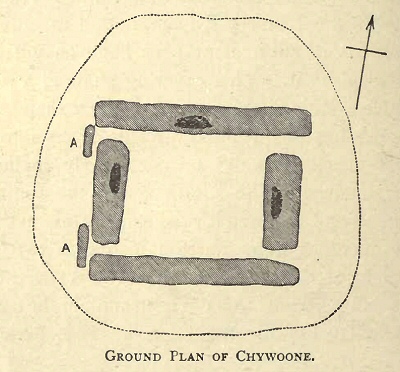

William Copeland Borlase gives a good account of his investigation at Chun Quoit in his book Naenia Cornubiae published in 1872 but gets his orientations wrong for some reason. Rather than trying to précis it I've transcribed it here in full (I've added line breaks for legibility and added the correct orientations in italics, the compass arrow in the inset plan should be rotated about 90 degrees anti-clockwise). The use of the word 'Cromlech' here means burial chamber monuments in general and 'Kist', which comes from the Welsh 'cistvaen' meaning the actual box formation of the chamber itself.

'Thinking this monument the most worthy of a careful investigation of all the Cromlechs in the neighbourhood, the author proceeded to explore it in the summer of 1871, with a view to determine, if possible, the method and means of erection in the case of such structures in general.

Sinking a pit by the side of the western (this should read north-western) stone, it was first of all discovered that the building rested on the solid ground, and not on the surrounding tumulus in which it had been subsequently buried. The Kist, as it seems, was formed in the following manner: The two upright stones forming the east and west (this should read southeast and northwest) ends of the chamber were the first to be set up, at a distance of about six feet apart; the breadth of the latter is four feet, and of the former 3 feet 10 inches, while the height of both is as nearly as possible the same, 6 feet 4 inches.

Sinking a pit by the side of the western (this should read north-western) stone, it was first of all discovered that the building rested on the solid ground, and not on the surrounding tumulus in which it had been subsequently buried. The Kist, as it seems, was formed in the following manner: The two upright stones forming the east and west (this should read southeast and northwest) ends of the chamber were the first to be set up, at a distance of about six feet apart; the breadth of the latter is four feet, and of the former 3 feet 10 inches, while the height of both is as nearly as possible the same, 6 feet 4 inches.

Another flat block of granite, 8 feet 4 inches long, was then set up in a slanting position against their northern (this should read northeast) edges, precisely as one places the third card in building a card box, serving at the same time as a part of the fabric, and as a stay or hold-fast to the sides against which it rests. It was from this side, no doubt, and probably over this slanting stone, that, with the assistance of an embankment and rollers, the cap-stone was raised into its present situation, from which, unlike Humpty Dumpty, in the Nursery Rhyme, not all the adverse combinations of subsequent ages have as yet been able to displace it.

This covering stone is a rough slab of hard-grained granite, of a convex shape, and, if the meaning of "vaulted" really enters into the word Cromlech, it would be particularly applicable in this instance. The length across the centre is twelve feet, and the breadth the same, while in thickness it averages from fourteen inches to two feet.

The height of the interior of the Kist is seven feet; and a small pit seems to have been sunk in the centre, below the level of the natural soil. It is here that the interment in all probability originally rested, and the chamber was then completed by a fifth stone (7 feet 8 inches long) thrown against the south(this should read southwest) side, but not reaching sufficiently high to come in contact with the covering stone.

The barrow or cairn, which in some places nearly reaches the top of the side stones on the exterior, is thirty-two feet in diameter, and was hedged round by a ring of upright stones. In digging down some of this pile from the sides of the monument, it was discovered that the interstices between the side stones had been carefully protected by smaller ones, placed in such a manner as to make it impossible for any of the rubbish of the mound to find its way into the kist. This arrangement will be better understood by referring to the letters A A in the accompanying plan, and is very suggestive of the whole being once totally buried in the tumulus.

Among the heap of stones a small fractured piece of flint was discovered. Its shape, however, does not lead to the supposition that it was ever used as an instrument of any kind. A round cavity on the capstone seems to have been a work of modern times, and was probably the socket of a pole during the survey.'

Site Visits / Photographs:

August 1997.

References:

Borlase, W. 1769. Antiquities, Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall. London

Borlase, W. C. 1872. Naenia Cornubiae A Descriptive Essay. London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer.

Cope, J. 1998. The Modern Antiquarian. A Pre-Millennial Odyssey through Megalithic Britain. London: Thorsons.

Cotton, W. 1827. Illustrations of Stone Circles, Cromlechs ... in the West of Cornwall. London: James Moyes.

Daniel, G. 1958. The Megalith Builders of Western Europe. London: Hutchinson and Co.

Halliwell, J. O. 1861. Rambles in Western Cornwall. London: John Russell Smith.

Hawkes, J. 1986. The Shell Guide to British Archaeology. London: Michael Joseph Ltd.

Lynch, F. 1997. Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications Ltd.

Weatherhill, C. 1981. Belerion. Ancient Sites of Land's End. Penzance: Alison Hodge.

Weatherhill, C. 1985. Cornovia. Ancient Sites of Cornwall & Scilly. Penzance: Alison Hodge.

Historic England research records Hob Uid: 424230. Cornwall & Scilly HER Number: 30518. NMR Number: SW 43 SW 29