About a mile and a quarter (2km) north of both the famous stone circle and standing stone of Long Meg and her Daughters and the tiny cairn of Little Meg with its decorated kerb stone are the remains at Glassonby of what could be interpreted as a round cairn enclosing an almost continuous ring of stones. The monument is located towards the northern edge of a platform of land that stands between the higher ground around Glassonby village to the southeast and the stream of Glassonby Beck 500 metres to the north, not far from its confluence with the River Eden.

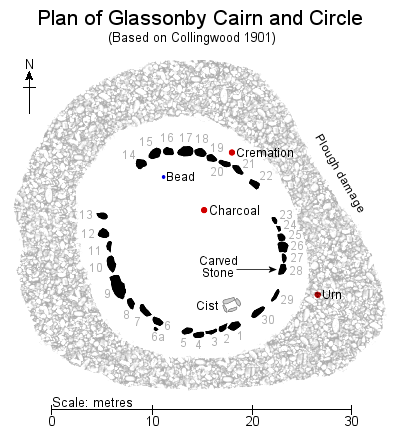

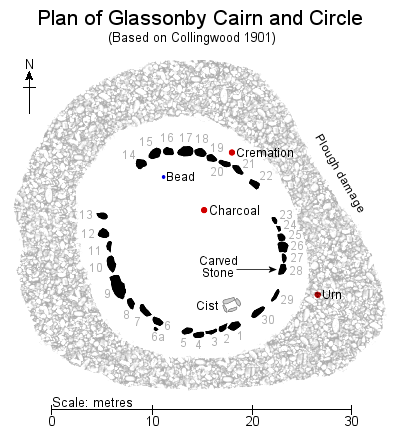

Today the covering mound of cobbles

that would have formed the cairn has almost completely vanished having been removed when the site was excavated

at the turn of the 20th century (plan left), it now measures less than half a metre in height and is estimated to have had

a diameter of about 30 metres.

Today the covering mound of cobbles

that would have formed the cairn has almost completely vanished having been removed when the site was excavated

at the turn of the 20th century (plan left), it now measures less than half a metre in height and is estimated to have had

a diameter of about 30 metres.

Within the remains of the mound are thirty close-set stones laid out in a rough oval measuring about 16 metres southeast to northwest by 14 metres southwest to northeast (the photograph above shows the southern and eastern arc of stones). In places the stones form an almost contiguous kerb while in other places large gaps suggest stones have been removed, perhaps for building material although it is possible that some of these gaps may have been intentional features of the original construction. While some of the stones stand nearly a metre tall many others tend to disappear under long grass in late summer.

What the original form of the monument was and it's sequence of construction is not clear. The ring of stones may have formed a kerb around the outer edge of a central cairn that was later monumentalised by the addition of an outer ring of cobbles. However alternatively the stones may have been set into the inner edge of an exterior ring cairn, the open interior being filled with cobbles at a later date perhaps marking the final closing of the monument. A third, although probably unlikely interpretation, might see the cairn as a single-phase construction, with the ring of stones either buried underneath the cairn in a single episode or perhaps left with the stone tops left exposed to produce an unusual and prominent hybrid monument.

During the excavation of the site in 1900 as recorded by W. Collingwood in 1901 but supervised by the Rev. Canon Thornley, incumbent of the parish of Kirkoswald, a cist was discovered within the ring of stones towards its south-eastern end. Collingwood reports the cist was formed of four red sandstone slabs laid out to form the sides of a rectangular box structure (presumably dug into the original ground surface) measuring just under a metre in length, 50 cm wide and up to 60 cm deep. What was assumed to be the cover to the cist was found nearby broken into three pieces which together with the fact that there were no remains within the cist itself suggested that it had been previously opened and its contents, which may have consisted of cremation remains, disarticulated bones or perhaps a child's inhumation, had been cleared out.

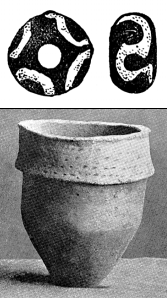

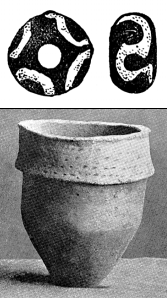

North of the centre of the ring an area of charcoal was discovered at ground level, although its dimensions are not recorded while towards the northwest a single blue and white faience bead was recovered 'at or near the original surface' (top image left). Although the bead may date to the Bronze Age and have been deliberately placed in the cairn it may also belong to either later prehistory or even the Roman period and given its small size we can't rule out the possibility that it fell through the stones of the cairn during excavation.

North of the centre of the ring an area of charcoal was discovered at ground level, although its dimensions are not recorded while towards the northwest a single blue and white faience bead was recovered 'at or near the original surface' (top image left). Although the bead may date to the Bronze Age and have been deliberately placed in the cairn it may also belong to either later prehistory or even the Roman period and given its small size we can't rule out the possibility that it fell through the stones of the cairn during excavation.

Just over 3 metres beyond the circle to the southeast an inverted collared urn dating from the early Bronze Age was found (bottom image left) that contained a quantity of charcoal, burned bones and twenty-four human teeth, these remains were later interpreted as being from an adult male. A further quantity of burned bones were found in a pit dug into the original ground surface just over a metre to the northeast of the ring, these could not be assigned a definite gender being considered to be either from a young male or a female. Given the contrast between the internal cist with its presumed lost human remains and the external urn and pit burials it is tempting to assign these to two separate deposition episodes and perhaps to different burial traditions which may support a two-phase cairn interpretation. Which were the primary and which were secondary interments however remains unanswered.

A detail that apparently went unnoticed until after the excavation was that one of the stones on eastern circumference of the ring had a series of faint carvings or rock art on its inner face (Stone 28 in Collingwood numbering system on the plan above and shown in the two photographs below). Its main design is a central group of four concentric rings with two further sets of four concentric rings emerging from the top of the central carving. There is another set of eroded rings above and between these last two features. Underneath these motifs are four upwards pointing chevrons and to the left are a set of grooves, although many of these could be interpreted as natural features.

None of the designs on this rock are easy to see and in some light conditions they are almost invisible - spot the carvings in my photograph? No, me neither. They are very finely cut and appear to have be clearer when first exposed although the motifs had to be 'touched up' for the black and white photograph published by Thornley in 1902. However it does seem that they have either been effected by erosion or have become partly obscured by lichen growth since that time. Thornley reported the diameter of the lower circle as 21 cm and the height of the whole design as 29cm although he only seems to have recognised three of the four groups of circles that Beckensall later recorded.

The fact that the carvings occur on the inner face of the stone may be significant. If the ring formed a revetment kerb around the outside of a cairn then it might suggest that the carvings were not meant to be see by the eyes of people outside of it, but by the deceased interred within the cist. Alternatively if the stone was set into the inner edge of a ring cairn they would only have been visible to those conducting ceremonies from within what may have been regarded as a sanctified space.

The designs on the stone are unusual as they are not in the 'cup and ring' tradition that is commonly associated with open air sites elsewhere but show more affinities with carvings found within Neolithic passage graves (there are similar examples within the chamber of Barclodiad y Gawres in Wales) and they can be compared to decorated stones at sites much further afield such as at Newgrange and Knowth in Ireland. As the material finds from the site point to a Bronze Age date does this mean that Glassonby is actually a multi-period monument that was used and re-modeled over a long period of time or was the carved stone brought in from an earlier and now lost Neolithic monument?

An alternative explanation may relate to Glassonby's wider geographical location as the site stands on the same narrow terrace of land sandwiched between the western Pennines and the River Eden as the nearby Long Meg and Little Meg both of which feature atypical rock carvings. The Eden eventually flows into the Solway Firth towards the north-eastern end of the Irish Sea. Together with the stylistic similarities with Irish rock art this has led to the suggestion that the Eden could have been the conduit that allowed an influx of Irish influences, if not settlers themselves, brought to the very edge of the Pennines in the second and third millennium BC.

Collingwood's report also contains a tantalising reference to a possible second carved stone at Glassonby. He states that a local man, a Mr. Thomas Glaister, recalled that about 25 years previously (so around 1875) a stone located between either Stones 30 and 1 or between Stones 5 and 6 had 'a spiral or concentric circles' inscribed upon its side. As this stone is now missing the report can't be verified and apart from the stone being described as red sandstone the description is vague enough to fit the remaining carved Stone 28 (which Collingwood records as consisting of cobble-stone). Until this mystery stone turns up, either in a nearby garden or hidden away at the back of a museum storeroom we can't be sure if Glaister was mistaken or not in his recollections of a quarter of a century earlier.

Today the covering mound of cobbles

that would have formed the cairn has almost completely vanished having been removed when the site was excavated

at the turn of the 20th century (plan left), it now measures less than half a metre in height and is estimated to have had

a diameter of about 30 metres.

Today the covering mound of cobbles

that would have formed the cairn has almost completely vanished having been removed when the site was excavated

at the turn of the 20th century (plan left), it now measures less than half a metre in height and is estimated to have had

a diameter of about 30 metres. Within the remains of the mound are thirty close-set stones laid out in a rough oval measuring about 16 metres southeast to northwest by 14 metres southwest to northeast (the photograph above shows the southern and eastern arc of stones). In places the stones form an almost contiguous kerb while in other places large gaps suggest stones have been removed, perhaps for building material although it is possible that some of these gaps may have been intentional features of the original construction. While some of the stones stand nearly a metre tall many others tend to disappear under long grass in late summer.

What the original form of the monument was and it's sequence of construction is not clear. The ring of stones may have formed a kerb around the outer edge of a central cairn that was later monumentalised by the addition of an outer ring of cobbles. However alternatively the stones may have been set into the inner edge of an exterior ring cairn, the open interior being filled with cobbles at a later date perhaps marking the final closing of the monument. A third, although probably unlikely interpretation, might see the cairn as a single-phase construction, with the ring of stones either buried underneath the cairn in a single episode or perhaps left with the stone tops left exposed to produce an unusual and prominent hybrid monument.

During the excavation of the site in 1900 as recorded by W. Collingwood in 1901 but supervised by the Rev. Canon Thornley, incumbent of the parish of Kirkoswald, a cist was discovered within the ring of stones towards its south-eastern end. Collingwood reports the cist was formed of four red sandstone slabs laid out to form the sides of a rectangular box structure (presumably dug into the original ground surface) measuring just under a metre in length, 50 cm wide and up to 60 cm deep. What was assumed to be the cover to the cist was found nearby broken into three pieces which together with the fact that there were no remains within the cist itself suggested that it had been previously opened and its contents, which may have consisted of cremation remains, disarticulated bones or perhaps a child's inhumation, had been cleared out.

North of the centre of the ring an area of charcoal was discovered at ground level, although its dimensions are not recorded while towards the northwest a single blue and white faience bead was recovered 'at or near the original surface' (top image left). Although the bead may date to the Bronze Age and have been deliberately placed in the cairn it may also belong to either later prehistory or even the Roman period and given its small size we can't rule out the possibility that it fell through the stones of the cairn during excavation.

North of the centre of the ring an area of charcoal was discovered at ground level, although its dimensions are not recorded while towards the northwest a single blue and white faience bead was recovered 'at or near the original surface' (top image left). Although the bead may date to the Bronze Age and have been deliberately placed in the cairn it may also belong to either later prehistory or even the Roman period and given its small size we can't rule out the possibility that it fell through the stones of the cairn during excavation.Just over 3 metres beyond the circle to the southeast an inverted collared urn dating from the early Bronze Age was found (bottom image left) that contained a quantity of charcoal, burned bones and twenty-four human teeth, these remains were later interpreted as being from an adult male. A further quantity of burned bones were found in a pit dug into the original ground surface just over a metre to the northeast of the ring, these could not be assigned a definite gender being considered to be either from a young male or a female. Given the contrast between the internal cist with its presumed lost human remains and the external urn and pit burials it is tempting to assign these to two separate deposition episodes and perhaps to different burial traditions which may support a two-phase cairn interpretation. Which were the primary and which were secondary interments however remains unanswered.

A detail that apparently went unnoticed until after the excavation was that one of the stones on eastern circumference of the ring had a series of faint carvings or rock art on its inner face (Stone 28 in Collingwood numbering system on the plan above and shown in the two photographs below). Its main design is a central group of four concentric rings with two further sets of four concentric rings emerging from the top of the central carving. There is another set of eroded rings above and between these last two features. Underneath these motifs are four upwards pointing chevrons and to the left are a set of grooves, although many of these could be interpreted as natural features.

None of the designs on this rock are easy to see and in some light conditions they are almost invisible - spot the carvings in my photograph? No, me neither. They are very finely cut and appear to have be clearer when first exposed although the motifs had to be 'touched up' for the black and white photograph published by Thornley in 1902. However it does seem that they have either been effected by erosion or have become partly obscured by lichen growth since that time. Thornley reported the diameter of the lower circle as 21 cm and the height of the whole design as 29cm although he only seems to have recognised three of the four groups of circles that Beckensall later recorded.

The fact that the carvings occur on the inner face of the stone may be significant. If the ring formed a revetment kerb around the outside of a cairn then it might suggest that the carvings were not meant to be see by the eyes of people outside of it, but by the deceased interred within the cist. Alternatively if the stone was set into the inner edge of a ring cairn they would only have been visible to those conducting ceremonies from within what may have been regarded as a sanctified space.

The designs on the stone are unusual as they are not in the 'cup and ring' tradition that is commonly associated with open air sites elsewhere but show more affinities with carvings found within Neolithic passage graves (there are similar examples within the chamber of Barclodiad y Gawres in Wales) and they can be compared to decorated stones at sites much further afield such as at Newgrange and Knowth in Ireland. As the material finds from the site point to a Bronze Age date does this mean that Glassonby is actually a multi-period monument that was used and re-modeled over a long period of time or was the carved stone brought in from an earlier and now lost Neolithic monument?

An alternative explanation may relate to Glassonby's wider geographical location as the site stands on the same narrow terrace of land sandwiched between the western Pennines and the River Eden as the nearby Long Meg and Little Meg both of which feature atypical rock carvings. The Eden eventually flows into the Solway Firth towards the north-eastern end of the Irish Sea. Together with the stylistic similarities with Irish rock art this has led to the suggestion that the Eden could have been the conduit that allowed an influx of Irish influences, if not settlers themselves, brought to the very edge of the Pennines in the second and third millennium BC.

Collingwood's report also contains a tantalising reference to a possible second carved stone at Glassonby. He states that a local man, a Mr. Thomas Glaister, recalled that about 25 years previously (so around 1875) a stone located between either Stones 30 and 1 or between Stones 5 and 6 had 'a spiral or concentric circles' inscribed upon its side. As this stone is now missing the report can't be verified and apart from the stone being described as red sandstone the description is vague enough to fit the remaining carved Stone 28 (which Collingwood records as consisting of cobble-stone). Until this mystery stone turns up, either in a nearby garden or hidden away at the back of a museum storeroom we can't be sure if Glaister was mistaken or not in his recollections of a quarter of a century earlier.

The carved rock with inset plan based on Beckensall 2002.

An image of the Glassonby carved stone credited to a Mr. F. W. Tassel and published in the Thornley's 1902 report. The accompanying text states that the carvings were 'very carefully retouched on the spot...Without this retouching the faint marks would hardly have been visible'.

In the old accounts the field the Glassonby monument stands is called either Grayson-Lands or Grazing Lands, one would appear to be a corruption of the other.

A line drawn along the long axis of the ring of stones at Glassonby roughly aligns with the co-ordinates given for a now destroyed cairn at Old Parks, 600 metres away to the north-northwest on the other side of Glassonby Beck. When the cairn was excavated it was found to contain a north-south line of five standing stones, three of which were decorated with rock carvings. Two of these stones are now in the Tullie House Museum in Carlisle with the third stone unfortunately having been lost (see Beckensall 2002, Plates 113, 114, 115). However the carvings are very different to those on the Glassonby stone, consisting of more abstract grooves and possible geometric shapes that are closer to the 'cup and ring' tradition often found at open air sites but which at Old Parks are found in association with a covered cremation cemetery. What is also unusual is that beneath the cairn no less than thirty-two deposits of cremated bone had been placed into hollows in the ground surface, but only on the western side of the line of standing stones. To the east two deep trenches cut east to west were assumed to be graves but no human remains were found in them except for 'some burnt bones and ashes' beneath a flagstone in the corner of the larger of the trenches. A single large urn containing cremation remains was found towards the south of the cairn and two incense cups, one of which contained twelve beads of 'cannel coal' as well as fragments of a further urn were found to the north (Ferguson, 1895).

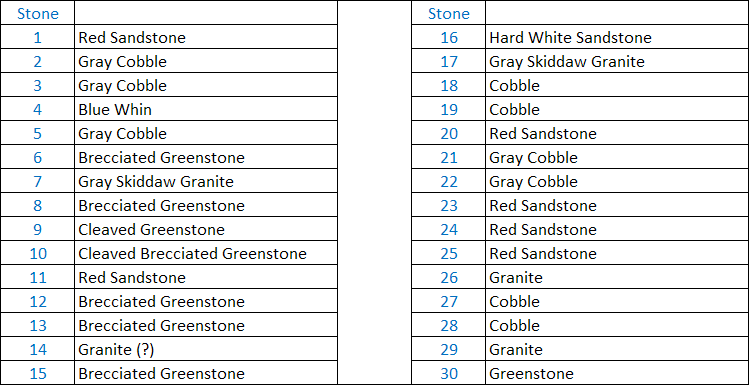

Table 1: Geological composition of the Glassonby stones after Collingwood 1901.

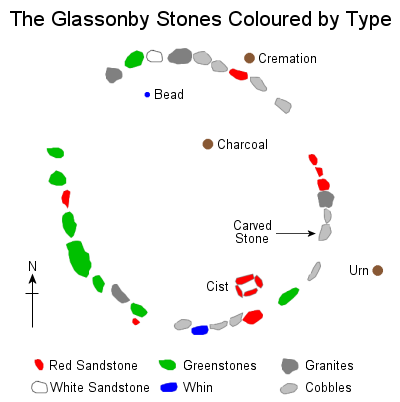

In her Doctoral thesis Penelope Foreman proposes that prehistoric monument builders across Europe may have carefully chosen stones not just for their shape and size but also their colouration and that coloured stones may have communicated a meaning that was widely understood in prehistory but that we can only guess at now. With this in mind and given that Collingwood's report attempted to identify the composition of the stones at Glassonby (Table 1 above) I thought it might be a useful exercise to add colour the plan of the site to see if it produced any meaningful results beyond just a pretty picture. I later found out that Kate Sharpe had beat me to it and produced an almost identical image to mine in her Doctoral thesis from 2007, such is archaeology, but its nice to come up with the same result as someone who knows much more about Cumbrian prehistory than I do.

The plan is shown left but with three caveats: firstly, several stones appear to be missing from the site so their composition is necessarily unknown, secondly we are relying on Collingwood's ability to identify the various stone types and thirdly, I'm not a geologist (but I'm quite happy to be corrected by someone who is).

The plan is shown left but with three caveats: firstly, several stones appear to be missing from the site so their composition is necessarily unknown, secondly we are relying on Collingwood's ability to identify the various stone types and thirdly, I'm not a geologist (but I'm quite happy to be corrected by someone who is). Several things are immediately clear, that most, but not all of the greenstone types are located to the west of the ring whereas most, but not all, of the 'grey' stone types (granites, cobbles) are located to the north, east and south. The single whin stone stands at due south, the white sandstone stands almost opposite, close, but not quite at the north. The red sandstones are fairly evenly spread except for a run of three stones towards the east. As sandstone splits easily (possibly the reason it was used for the slabs of the cist) these may have originally been broken from a single stone by the builders. Interestingly the area of charcoal within the ring and the cremation just beyond the ring sandwich a single piece of red sandstone. As a paper exercise, if a line is draw through these three points and extended north-eastwards it passes close to the prominent peak of Thack Moor just under 5 miles away, the caveat here being the level of accuracy of the original plan.

So, do the results suggest anything? It is just possible that the stones were deliberately placed to form discrete zones, particularly a grey/green, east/west division which would make an interesting comparison to the striking east/west division seen at Old Parks while the other stones may mark points in the landscape that held symbolism for the local population or perhaps even pointed to celestial alignments. However a more prosaic explanation may involve geology and economy of effort, if glacial action had deposited most of the greenstone boulders to the west of the site and the granites and cobble to the east, then would the builders have gone to the effort of dragging the stones any further than necessary to construct the monument?

Site Visits / Photographs:

August 2003.

References:

Barnatt, J. 1987. The Design and Distribution of Stone Circles... Thesis, (PhD). University of Sheffield.

Barnes, H. 1901. On the Bones from Grayson-lands Tumulus... TCWAAS, Series 2, Vol 1, 300-302.

Beckensall, S. 1999. British Prehistoric Rock Art. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Beckensall, S. 2002. Prehistoric Rock Art in Cumbria. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Bradley, R. 1993. Altering the Earth. Soc. Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph 8. Stroud: Sutton.

Bradley, R. 1997. Rock Art and the Prehistory of Atlantic Europe. London: Routledge.

Burl, A. 1995. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. London: Yale University Press.

Clare, T. 2007. Prehistoric Monuments of the Lake District. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Cope, J. 2004. The Megalithic European. London: Element / Harper Collins.

Collingwood, W. 1901. Tumulus at Grayson-lands, Glassonby.... TCWAAS, Series 2, Vol 1, 295-299.

Evans, I. 2005. Prehistoric Landscapes of Cumbria. Thesis, (PhD). University of Sheffield.

Farrah, R.W.E. 2008. A guide to the Stone Circles of Cumbria. Kirkby Stephen: Hayloft Publishing Ltd.

Ferguson, R. 1895. On a Tumulus at Old Parks, Kirkoswald... TCWAAS, Series 1, Vol 13, 389-399.

Foreman, P. 2019. Colour Out of Space: Colour in the Construction... Thesis, (PhD). Bournemouth Uni.

Frodsham, P. 1989. Two Newly Discovered Cup and Ring Marked Stones... TCWAAS, Series 2, Vol 89, 1-19.

Gibson, A. 1986. Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Pottery. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Ibbotson, A. 2021. Cumbria's Prehistoric Monuments. Stroud: The History Press.

Sharpe, K. 2007 Motifs, monuments and mountains: prehistoric rock art ... Thesis, (PhD). Durham.

Shee Twohig, E. 2004. Irish Megalithic Tombs. Second Edition. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Smith, R. 2015. Neolithic rock-art in the north of Europe... Thesis, (PhD). University of Liverpool

Thornley, J. 1902. Ring-marked Stones at Glassonby and Maughanby. TCWAAS, Series 2, Vol 2, 380-383.

TCWAAS = Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society.