Stonehenge - looking due south from beside the A344 road in early evening sunshine. |

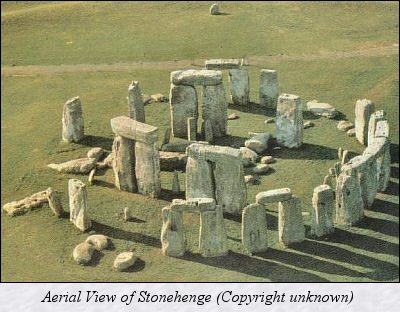

The

most famous prehistoric structure in Europe, possibly the world,

Stonehenge stands on Salisbury Plain, an area rich in monuments

such as long

barrows and round

barrows. It draws visitors from all over the world but viewing

is restricted and it is difficult to get a sense of the grandeur

of the place amongst all of the tourists. The

most famous prehistoric structure in Europe, possibly the world,

Stonehenge stands on Salisbury Plain, an area rich in monuments

such as long

barrows and round

barrows. It draws visitors from all over the world but viewing

is restricted and it is difficult to get a sense of the grandeur

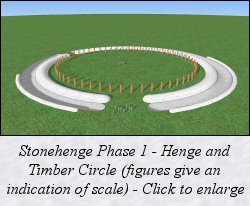

of the place amongst all of the tourists.There have been many timescales attached to the building of the site although it is generally held to have been completed in three identifiable phases over a 1500 year period starting perhaps around 3000BC. The exact sequence of these phases and indeed their sub phases has changed over the years as new evidence from excavation has come to light and absolute dating techniques such as radiocarbon C14 have been applied. The following sequences are based on those proposed by Cleal, Walker and Montague whose work was published in 1995 and accepted by many as currently the most complete picture of construction at the site. Interpretations of exactly what each of these successive changes meant to the builders however are open to conjecture. Stonehenge Phase 1 (2950-2900BC) Begun in the late Neolithic, a circular bank nearly 2 metres high and 6 metres wide and with an internal diameter of 85 metres was built with chalk quarried from an outer ditch, the bright white fresh chalk contrasting vividly against the surrounding grassland.  The ditch would have been hacked out of the chalk with antler picks

and appears to have been cut in individual sections, perhaps echoing

the earlier style of monuments known as causewayed enclosures. However

here these sections were then joined together to produce a continuous

trench about 7 metres wide and 2 metres deep with a causeway or

entrance about 4 metres wide to the south and another of 10 metres

wide towards the northeast. It is this earthwork structure that

give the name 'henge'

to other similar monuments elsewhere in the country but unusually

at Stonehenge the bank is internal and the ditch external, elsewhere

henges have internal ditches and external banks. Stonehenge does

have a small external counterscarp bank around the outer edge of

the ditch but this appears to only surround the north and eastern

sections and may only have been a low mound about 2 or 3 metres

in width.

The ditch would have been hacked out of the chalk with antler picks

and appears to have been cut in individual sections, perhaps echoing

the earlier style of monuments known as causewayed enclosures. However

here these sections were then joined together to produce a continuous

trench about 7 metres wide and 2 metres deep with a causeway or

entrance about 4 metres wide to the south and another of 10 metres

wide towards the northeast. It is this earthwork structure that

give the name 'henge'

to other similar monuments elsewhere in the country but unusually

at Stonehenge the bank is internal and the ditch external, elsewhere

henges have internal ditches and external banks. Stonehenge does

have a small external counterscarp bank around the outer edge of

the ditch but this appears to only surround the north and eastern

sections and may only have been a low mound about 2 or 3 metres

in width.  The

entire diameter of the earthworks was hence about 115 metres. Excavations

around the southern entrance revealed a pair of ox jaw bones had

been placed in the ditch on either side of the causeway along with

an ox skull further to the west of the entrance and a deer tibia

to the east. Radiocarbon dating shows that these remains The

entire diameter of the earthworks was hence about 115 metres. Excavations

around the southern entrance revealed a pair of ox jaw bones had

been placed in the ditch on either side of the causeway along with

an ox skull further to the west of the entrance and a deer tibia

to the east. Radiocarbon dating shows that these remains  predate

the digging of the earthwork by as much as several hundred years

suggesting they had been preserved as venerated objects or had perhaps

been taken from collections of bones from the preexisting long barrows

of Salisbury Plain. predate

the digging of the earthwork by as much as several hundred years

suggesting they had been preserved as venerated objects or had perhaps

been taken from collections of bones from the preexisting long barrows

of Salisbury Plain.Also during this phase of construction a ring of fifty-six pits were cut about 5 metres away from the inner edge of the bank. These have been named the 'Aubrey Holes' after their discoverer John Aubrey who originally noticed five circular depressions in 1666 although it was not until the 1920's that their full extent was confirmed and recorded. There is some debate as to whether these pits ever held wooden posts or stones that were later removed. Stonehenge Phase 2 (2900-2600BC) It appears that there was a hiatus in construction at the site at the beginning of Phase 2, the ditch was allowed to silt up and if there were timber posts in the Aubrey Holes then these were either removed or rotted away. Later there was some deliberate backfilling of the ditch and the height of the bank was also reduced somewhat.  It

was during this phase that excavations have revealed a series of

timber posts and structures were erected, although what these post

actually represented is unclear. The posts are clustered in three

areas, the northeast entrance, the southern entrance and the central

area of the henge. Roughly in line with the ditch the causeway of

the northeastern entrance shows evidence of between seven and nine rows

of posts set along a southwest-northeast alignment, and it has been

suggested that they formed setting out lines for the observation

of the major and minor northern moonrises, another set of four posts

that stood about 15 metres northeast could also have been involved

with following the movements of the moon. An alternative explanation

is that these posts formed the lines of a series of fences allowing

or blocking entrance into the central area of the henge. The use

of posts to form an entrance corridor does seem to occur near the

southern entrance through the earthwork. Here the roughly south-north

rectangular arrangement which could have been fenced meets several

rows of posts set at a perpendicular angle which may represent further

fences or temporary screens. What it was in the central area that

was hidden from view is difficult to determine, timber buildings

are possible but the many post holes found here do not seem to form

any recognisable structures and disturbance of the ground during

the subsequent stone building episodes means that whatever these

post holes originally represented remains a mystery. It

was during this phase that excavations have revealed a series of

timber posts and structures were erected, although what these post

actually represented is unclear. The posts are clustered in three

areas, the northeast entrance, the southern entrance and the central

area of the henge. Roughly in line with the ditch the causeway of

the northeastern entrance shows evidence of between seven and nine rows

of posts set along a southwest-northeast alignment, and it has been

suggested that they formed setting out lines for the observation

of the major and minor northern moonrises, another set of four posts

that stood about 15 metres northeast could also have been involved

with following the movements of the moon. An alternative explanation

is that these posts formed the lines of a series of fences allowing

or blocking entrance into the central area of the henge. The use

of posts to form an entrance corridor does seem to occur near the

southern entrance through the earthwork. Here the roughly south-north

rectangular arrangement which could have been fenced meets several

rows of posts set at a perpendicular angle which may represent further

fences or temporary screens. What it was in the central area that

was hidden from view is difficult to determine, timber buildings

are possible but the many post holes found here do not seem to form

any recognisable structures and disturbance of the ground during

the subsequent stone building episodes means that whatever these

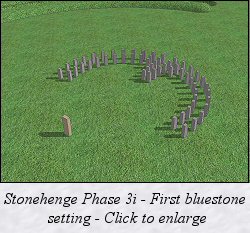

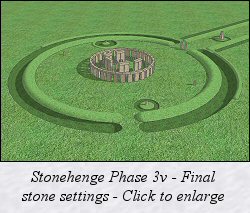

post holes originally represented remains a mystery. Excavation of thirty-four of the Aubrey Holes has revealed that twenty-five of them contained cremation remains that date from this phase of the site indicating that the holes were still visible features in the landscape. Fragments of pottery show that these deposits belonged to people associated with the Grooved Ware culture and were mostly found towards the eastern side of the monument, other small pits with cremated remains placed in them have been uncovered in the bottom of the ditch and just within the inside of the bank, again these are nearly all found on the eastern side of the earthwork. Stonehenge Phase 3 (2600-1600BC) It is in this third stage of construction spanning the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age that the stones for which the site is so famous finally arrive. As is so often the case at Stonehenge the exact sequences and timescales are subject to debate and reassessment as more evidence comes to light. Phase 3i The first stones to be set up within the henge earthwork are thought to be the bluestones (Phase 3i). The original layout appears to have been a pair of concentric semicircles with an average diameter of 25 metres in  the

centre of the monument with an opening towards the southwest. This

setting has been determined by the excavation of two sets of stones

pits known as the 'Q' and 'R' holes. This setting was however only

short lived with the stones then being removed and the holes backfilled

with chalk rubble. Possibly contemporary with this bluestone setting

is the erection of the Altar Stone to the southwest of the semicircle

which may have acted as a focal point of activity for the setting.

This brings us to the most contentious issue surrounding Stonehenge,

how these stones got here. About eighty bluestones were used at the

site and the rock for them came from different areas around the

Preseli mountains in southwest Wales (some possibly from Carn

Meini) over 135 miles away. They consists mainly of dolerite

and some of rhyolite, both types of volcanic rock with the stones

weighing up to 4 tons each. One theory is that they would have the

centre of the monument with an opening towards the southwest. This

setting has been determined by the excavation of two sets of stones

pits known as the 'Q' and 'R' holes. This setting was however only

short lived with the stones then being removed and the holes backfilled

with chalk rubble. Possibly contemporary with this bluestone setting

is the erection of the Altar Stone to the southwest of the semicircle

which may have acted as a focal point of activity for the setting.

This brings us to the most contentious issue surrounding Stonehenge,

how these stones got here. About eighty bluestones were used at the

site and the rock for them came from different areas around the

Preseli mountains in southwest Wales (some possibly from Carn

Meini) over 135 miles away. They consists mainly of dolerite

and some of rhyolite, both types of volcanic rock with the stones

weighing up to 4 tons each. One theory is that they would have been hauled from the mountains to Milford Haven and then loaded

onto rafts and brought along the Welsh coast to the Severn estuary,

then along the Bristol Avon and the River Frome, via the Wiltshire

Avon before being offloaded to the banks of the river. From here

they were brought overland to Stonehenge - a total journey distance

of 250 miles. The Altar Stone, a block of micaceous sandstone, is

thought to have originated from the Brecon Beacons area of south

Wales. The opposing theory is that a mixture of stone from west

Wales was moved eastwards by glaciation during one of the Ice Ages

to be deposited

been hauled from the mountains to Milford Haven and then loaded

onto rafts and brought along the Welsh coast to the Severn estuary,

then along the Bristol Avon and the River Frome, via the Wiltshire

Avon before being offloaded to the banks of the river. From here

they were brought overland to Stonehenge - a total journey distance

of 250 miles. The Altar Stone, a block of micaceous sandstone, is

thought to have originated from the Brecon Beacons area of south

Wales. The opposing theory is that a mixture of stone from west

Wales was moved eastwards by glaciation during one of the Ice Ages

to be deposited  around

the Salisbury Plain area as the ice sheets retreated. The builders

of Stonehenge then simply used sources of stone that were most readily

available, the bluestone that already existed in the Salisbury Plain

area. Both theories have faults and it is unlikely that a solution

to the problem will be agreed upon for some time. around

the Salisbury Plain area as the ice sheets retreated. The builders

of Stonehenge then simply used sources of stone that were most readily

available, the bluestone that already existed in the Salisbury Plain

area. Both theories have faults and it is unlikely that a solution

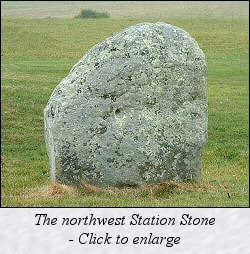

to the problem will be agreed upon for some time. Also dating from this phase were four sarsen blocks known as the Station Stones which were erected about 5 metres within the henge bank. Laid out in an almost perfect rectangle only two of these stones now remain but it appears that they were designed to align with the midsummer sunrise, midwinter sunset and the major northern moonset although lines drawn through these stones and a missing stone or post towards the east of the site suggest that other alignments may also have been intended. Phase 3ii-3v After the dismantling of the bluestone arc the stones for the sarsen circle and trilithons were brought from the Marlborough Downs, 25 miles to the north (Phase 3ii).  Roughly

cut to shape before moving, these huge blocks weighing between 6

and 50 tons each may have been placed on sledges and dragged over

rollers or temporary trackways to Stonehenge. It is estimated that

it would have taken a team of 1000 men seven weeks to move each stone,

the whole mammoth task requiring over ten years to complete. Once

at the site, the rough sarsen blocks would have been shaped by a

team of masons, another task that would have taken several years.

To create the Sarsen Circle pits of about 1.5 metres deep were cut

in a Roughly

cut to shape before moving, these huge blocks weighing between 6

and 50 tons each may have been placed on sledges and dragged over

rollers or temporary trackways to Stonehenge. It is estimated that

it would have taken a team of 1000 men seven weeks to move each stone,

the whole mammoth task requiring over ten years to complete. Once

at the site, the rough sarsen blocks would have been shaped by a

team of masons, another task that would have taken several years.

To create the Sarsen Circle pits of about 1.5 metres deep were cut

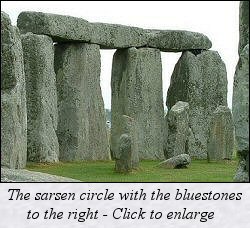

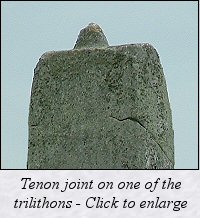

in a  30

metre diameter circle and the blocks tipped into them then pulled

upright and their tops leveled, but with a protruding tenon to receive

the lintels. These lintels had mortises on their undersides to fit

the uprights and tongue-and-groove joints to bind them to their

neighbours as well as a slight curve along their outer edges. The

Sarsen Circle dates from around 2500BC and consisted of thirty uprights

each weighing about 25 tons and standing 4 metres in height supporting

thirty lintels each weighing 6 tons and forming a ring whose top was

nearly 5 metres above ground level. Today only seventeen of the uprights

remain standing along with six lintels still in place which fortunately

includes the pair of uprights to the northeast that were set slightly

further apart than the other circle stones and formed the grand

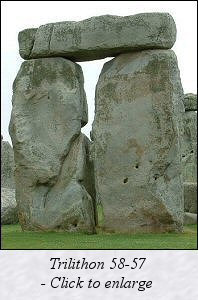

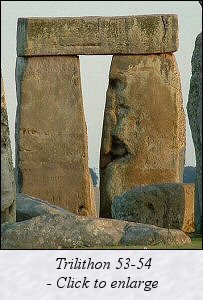

entrance into the inner sanctified area. Within the circle's interior

were raised the five huge sarsen trilithons

in a horseshoe setting whose open end facing towards the northeast,

each trilithon consisting of a pair of uprights whose tops where

also cut 30

metre diameter circle and the blocks tipped into them then pulled

upright and their tops leveled, but with a protruding tenon to receive

the lintels. These lintels had mortises on their undersides to fit

the uprights and tongue-and-groove joints to bind them to their

neighbours as well as a slight curve along their outer edges. The

Sarsen Circle dates from around 2500BC and consisted of thirty uprights

each weighing about 25 tons and standing 4 metres in height supporting

thirty lintels each weighing 6 tons and forming a ring whose top was

nearly 5 metres above ground level. Today only seventeen of the uprights

remain standing along with six lintels still in place which fortunately

includes the pair of uprights to the northeast that were set slightly

further apart than the other circle stones and formed the grand

entrance into the inner sanctified area. Within the circle's interior

were raised the five huge sarsen trilithons

in a horseshoe setting whose open end facing towards the northeast,

each trilithon consisting of a pair of uprights whose tops where

also cut  with

a single tenon to secure the mortised lintel. The horseshoe was

graduated in height towards the southwest with the northeast opposing

pair standing just over 6 metres tall, the inner pair 6.5 metres

and the southwest or 'Great Trilithon' towering to a massive with

a single tenon to secure the mortised lintel. The horseshoe was

graduated in height towards the southwest with the northeast opposing

pair standing just over 6 metres tall, the inner pair 6.5 metres

and the southwest or 'Great Trilithon' towering to a massive  7.3

metres high in total. It is the uprights of the Great Trilithon

that are the largest and heaviest stones on the site weighing in

at a staggering 50 tons. Sadly today only three of the trilithons stand

complete along with a single upright from the remaining pair. 7.3

metres high in total. It is the uprights of the Great Trilithon

that are the largest and heaviest stones on the site weighing in

at a staggering 50 tons. Sadly today only three of the trilithons stand

complete along with a single upright from the remaining pair. Although the earlier bluestone setting had been removed it is thought the Altar Stone was re-erected slightly to the northeast near the centre point of the circle within the sarsen horseshoe. The bluestones were now erected in an uncertain arrangement somewhere within the Sarsen Circle (Phase 3iii) before being removed and sixty of the stones placed in circular formation known as the Bluestone Circle between the trilithons and the sarsen circle (Phase 3iv). Within the horseshoe of trilithons a further twenty-three carefully shaped and dressed bluestones were initially set up in oval before those towards the northeast were removed to form the 'Bluestone Horseshoe', the stones graded in height towards the southwest echoing the layout of the larger sarsen trilithons (Phase 3v). Only six stones of this horseshoe remain standing plus eleven stones from the bluestone circle although just over twenty other bluestones remain as either stumps or fallen or broken stone fragments.   The

central area of Stonehenge was now in the layout we see it today

but other stones stand, or stood around the area of the northeastern

entrance that also date from Phase 3 although they cannot be precisely

placed within any of the five sub phases above. The most obvious

of these stones is the Heel Stone which stands 20 metres beyond

the entrance , a rough unshaped sarsen nearly 5 metres tall that

now leans inwards towards the circle. Excavations have revealed

that another stone once stood 2 metres to the northwest and together

this pair of stones formed a portal through which the midsummer

sun could be observed from the centre of Stonehenge as contrary

to popular belief the sunrise occurs just to the left of the Heel

Stone and not above it at the summer solstice. For some reason the

second stone was then removed with a ditch being cut around the

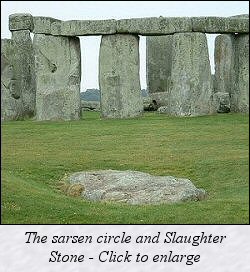

remaining Heel Stone. Just next to the entrance bank a fallen sarsen

known as the Slaughter Stone is the sole remainder of an alignment

of two or three uprights that once stood across the entrance. A

plan of Stonehenge drawn by Aubrey in 1666 shows a pair of stones

standing within this entrance but sixty years later William Stukeley

recorded only the Slaughter Stone which by now had been toppled

and its neighbour removed. The

central area of Stonehenge was now in the layout we see it today

but other stones stand, or stood around the area of the northeastern

entrance that also date from Phase 3 although they cannot be precisely

placed within any of the five sub phases above. The most obvious

of these stones is the Heel Stone which stands 20 metres beyond

the entrance , a rough unshaped sarsen nearly 5 metres tall that

now leans inwards towards the circle. Excavations have revealed

that another stone once stood 2 metres to the northwest and together

this pair of stones formed a portal through which the midsummer

sun could be observed from the centre of Stonehenge as contrary

to popular belief the sunrise occurs just to the left of the Heel

Stone and not above it at the summer solstice. For some reason the

second stone was then removed with a ditch being cut around the

remaining Heel Stone. Just next to the entrance bank a fallen sarsen

known as the Slaughter Stone is the sole remainder of an alignment

of two or three uprights that once stood across the entrance. A

plan of Stonehenge drawn by Aubrey in 1666 shows a pair of stones

standing within this entrance but sixty years later William Stukeley

recorded only the Slaughter Stone which by now had been toppled

and its neighbour removed. One

other major component of the Stonehenge landscape is also believed

to date from the third phase, the Stonehenge

Avenue is thought to have been built at some point during this

time although again where it fits in with the chronology is unclear.

Starting on the banks of the River Avon a mile and a quarter southeast

of Stonehenge it travels northwest, swings round to the west and

then makes a final turn in the depression of Stonehenge One

other major component of the Stonehenge landscape is also believed

to date from the third phase, the Stonehenge

Avenue is thought to have been built at some point during this

time although again where it fits in with the chronology is unclear.

Starting on the banks of the River Avon a mile and a quarter southeast

of Stonehenge it travels northwest, swings round to the west and

then makes a final turn in the depression of Stonehenge  Bottom

before making its final 500 metre approach up the slight slope to

the northeast entrance of the henge. This final section of the Avenue

has the same axis as the stones i.e. it forms a corridor or alignment

with the midsummer sunrise. Although the Heel Stone is the only

stone located within the Avenue's banks and ditches William Stukeley

noticed the traces of lines of stone holes which suggested that

a double row of stones also once ran along the inside of the earthwork,

perhaps fifty stones in all. The results of geophysics surveys in 1979-1980

would seem to support this view. Bottom

before making its final 500 metre approach up the slight slope to

the northeast entrance of the henge. This final section of the Avenue

has the same axis as the stones i.e. it forms a corridor or alignment

with the midsummer sunrise. Although the Heel Stone is the only

stone located within the Avenue's banks and ditches William Stukeley

noticed the traces of lines of stone holes which suggested that

a double row of stones also once ran along the inside of the earthwork,

perhaps fifty stones in all. The results of geophysics surveys in 1979-1980

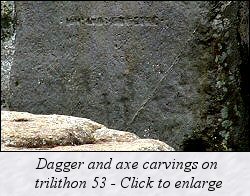

would seem to support this view.Phase 3vi Although no stones were added after Phase 3v there was a final bout of construction within the henge earthworks. Sometime between 1800-1600BC a double ring of pits were cut into the earth and chalk outside of the main stone setting. These have been termed the 'Z' and 'Y' holes and formed rather ragged and inaccurately laid out circles of 38 metres and 54 metres diameter respectively. There appears to be no evidence that these pits ever held stones although it has been suggested that they were designed to hold two rings of bluestones, perhaps the plan was abandoned as Stonehenge fell out of use finally bringing to an end 1500 years of building and remodeling at the site. In 1953 Professor Richard Atkinson who was carrying out excavations at the site made a  remarkable

discovery of a dagger carved into the face of one of the trilithon

uprights (stone 53) and beside it about a dozen faint carvings of

axe heads similar in design to Bronze Age flanged axes that are

known to date from this period in Stonehenge's history (about 1800BC).

Other markings have since been found on other stones, particularly

on one of the uprights of the sarsen circle which has possibly two

dozen axe heads carved into it and perhaps the carvings on these

stones were amongst some of the final acts that took place on the

site before the sun finally set on prehistoric activity at the site.

Over the 3500 years since then the stones fell into a long period

of gradual decay and dilapidation caused by the elements, damage

caused by accident as well as deliberate human destruction and the

robbing of stones for building material elsewhere. remarkable

discovery of a dagger carved into the face of one of the trilithon

uprights (stone 53) and beside it about a dozen faint carvings of

axe heads similar in design to Bronze Age flanged axes that are

known to date from this period in Stonehenge's history (about 1800BC).

Other markings have since been found on other stones, particularly

on one of the uprights of the sarsen circle which has possibly two

dozen axe heads carved into it and perhaps the carvings on these

stones were amongst some of the final acts that took place on the

site before the sun finally set on prehistoric activity at the site.

Over the 3500 years since then the stones fell into a long period

of gradual decay and dilapidation caused by the elements, damage

caused by accident as well as deliberate human destruction and the

robbing of stones for building material elsewhere.What

was Stonehenge built for? |

An early morning view of Stonehenge looking west. The outer sarsen circle of uprights and lintels are clearly visible but the bluestones are hidden and the trilithons are partly obscured from sight. |

Looking southwest from the end of the Stonehenge Avenue where it passes through the henge earthworks marking the entrance to the internal area and stones themselves. The fallen Slaughter Stone lies to the left. This view is looking towards the centre of the monument and marks the line of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset. |

View of Stonehenge looking south from close to the 'north barrow' and missing northern station stone. |

The less glamorous view of Stonehenge. Looking northeast roughly along the line of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset |

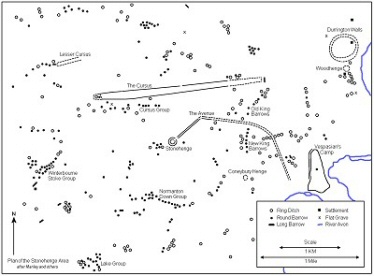

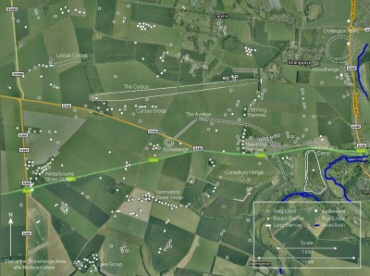

Left: The Stonehenge area. Right: Area map overlaid on satellite view. Click to see enlarged images. |

Stonehenge Interactive

Pages |

|

June 1988, September 2002, July 2011. Primary References: Atkinson, R. 1960. Stonehenge. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd. Burl, A. 1995. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. London: Yale University Press. Burl, A. 2007. A Brief History of Stonehenge. London: Robinson. Cleal, R., Walker, K. and Montague, R. 1995. Stonehenge in its landscape... London: English Heritage. Exon, S., Gaffney, V., Woodward, A. and Yorston, R. 2000. Stonehenge Landscapes. Oxford: Archaeopress. Gibson, A. 2005. Stonehenge and Timber Circles. New Edition. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. Lawson, A. 2007. Chalkland: an Archaeology of Stonehenge and its Region. Salisbury: The Hobnob Press. Manley, J. 1989. Atlas of Prehistoric Britain. Oxford: Phaidon Press Ltd. Parker Pearson, M. 2012. Stonehenge. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. Parker Pearson, M. and Ramilisonina. 1998. Stonehenge for the Ancestors... Antiquity, 72, 308-26. Pitts, M. 2001. Hengeworld. London: Arrow Books Ltd. Souden, D. 1997. Stonehenge Revealed. Collins and Brown Ltd. |

|

Back to Map | Home | Full Glossary | Links | Email: chriscollyer@stone-circles.org.uk

standstill in its 18.6 year cycle. This concentration on the moon

seems to have continued into Phase 2 when lines of posts were set

up in the entrance to allow move accurate observations. Later during

this phase the Aubrey Holes and the ditch and bank on the eastern

side of the earthwork begin to be used for the burial of cremation

remains. It is unclear whether the use of the site as a cremation

cemetery associated with the Grooved Ware culture was by incomers

to the area or by the local population who had adopted the new ideas

and beliefs. The beginning of Phase 3 marks a shift in both the ritual

and physical alignments of Stonehenge. Whereas the henge causeway

has an alignment of about 46.5 degrees from north the stones set up

within it are aligned slightly further east at just under 50 degrees

- the direction of the sunrise on the solstice, the longest day of

the year. This association of Stonehenge with the rising sun probably

continued throughout the remainder of its use in prehistory and continues

in modern times with the opening of the site to thousands of visitors

on the morning of the summer solstice. It seems that Stonehenge never

had just one use, as the years passed the people and the rituals enacted

within the earthwork and later within area enclosed by the stones

changed as the Neolithic moved slowly into the early Bronze Age. What

is left to us today gives only a tantalizing glimpse of what may have

happened at one of the worlds most enigmatic ancient sites.

standstill in its 18.6 year cycle. This concentration on the moon

seems to have continued into Phase 2 when lines of posts were set

up in the entrance to allow move accurate observations. Later during

this phase the Aubrey Holes and the ditch and bank on the eastern

side of the earthwork begin to be used for the burial of cremation

remains. It is unclear whether the use of the site as a cremation

cemetery associated with the Grooved Ware culture was by incomers

to the area or by the local population who had adopted the new ideas

and beliefs. The beginning of Phase 3 marks a shift in both the ritual

and physical alignments of Stonehenge. Whereas the henge causeway

has an alignment of about 46.5 degrees from north the stones set up

within it are aligned slightly further east at just under 50 degrees

- the direction of the sunrise on the solstice, the longest day of

the year. This association of Stonehenge with the rising sun probably

continued throughout the remainder of its use in prehistory and continues

in modern times with the opening of the site to thousands of visitors

on the morning of the summer solstice. It seems that Stonehenge never

had just one use, as the years passed the people and the rituals enacted

within the earthwork and later within area enclosed by the stones

changed as the Neolithic moved slowly into the early Bronze Age. What

is left to us today gives only a tantalizing glimpse of what may have

happened at one of the worlds most enigmatic ancient sites.