The facade and blocking stones of West Kennet viewed from the south east.

Known as a Cotswold-Severn type barrow after stylistic similarities found in other such monuments in the region, what we see today is a partial reconstruction that represents the combination of two phases of building activity at the site, firstly the original tomb and mound which were constructed during the middle of the Neolithic sometime around 3670BC and then the addition of massive sarsen blocking stones that marked the final closure of the tomb in about 2300BC as traditions and beliefs changed at the dawning of the Bronze Age.

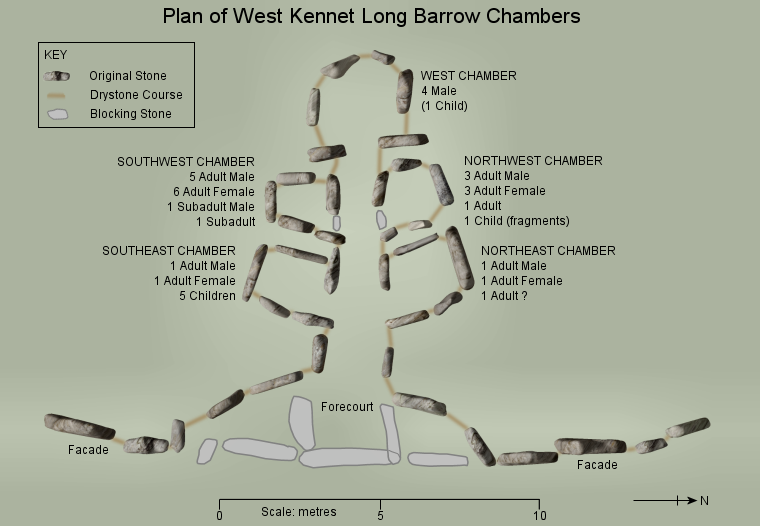

In the primary phase of building a transepted megalithic tomb was constructed of upright sarsen slabs (orthostats) arranged to form a passageway 8 metres long, 2.3 metre high and 1.3 metre wide which opened out into two chambers to the north, two to the south and a single terminal chamber to the west. Access to the tomb was by an entrance to the east where further orthostats were arranged into an impressive concave facade and forecourt that may acted as the focus for ceremonies in front of the tomb. As well as rites relating to the interment of bodies within the chambers these activities could also have included the periodic removal of bones to take place in ceremonies elsewhere, perhaps at the Causewayed Enclosure at Windmill Hill.

The chambers differed in size and shape, the northeast and northwest chambers being roughly square with internal areas of between 3 and 4 square metres, the chamber to the southeast was slightly more rectangular but occupied a similar internal area. The smaller southwest chamber was more of a trapezoid shape with an area of not much more than 2 square metres while the western terminal chamber was a much larger five or six sided construction with a ground surface covering nearly 7 square metres. For some reason the north and south chambers were not built perpendicular to the passage but instead inclined slightly to the west.

The chambers differed in size and shape, the northeast and northwest chambers being roughly square with internal areas of between 3 and 4 square metres, the chamber to the southeast was slightly more rectangular but occupied a similar internal area. The smaller southwest chamber was more of a trapezoid shape with an area of not much more than 2 square metres while the western terminal chamber was a much larger five or six sided construction with a ground surface covering nearly 7 square metres. For some reason the north and south chambers were not built perpendicular to the passage but instead inclined slightly to the west.

Gaps between the orthostats were filled with a mix of smaller sarsen boulders and rubble and lined at ground level with a course of drystone walling. While there were plentiful supplies of sarsen available locally from the Marlborough Downs the stone used for the drystone walling was instead limestone, believed to have been sourced from the area around Frome nearly 20 miles (30km) to the southwest. Further horizontal sarsen slabs were then used to form capstones over the chambers and passageway with more sarsen rubble firstly added around the structure to support the orthostats and then heaped up to form a cairn over the entire tomb.

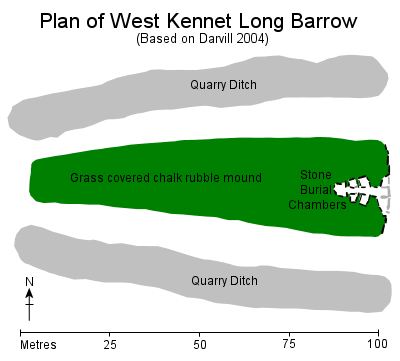

At this point chalk rubble was quarried from a pair of 5 metre wide, 3-4 metre deep flanking ditches and piled over the stone cairn to form the external body of the long barrow which was shaped into a trapezoidal mound oriented east to west with the chambers and entrance located at the eastern end. The barrow mound has suffered degradation over the millennia and it currently measures some 104 metres in length, tapering from a width of 25 metres at its eastern end to about 10 metres at the west and standing to a maximum height of just over 3 metres towards the east.

Each of the chambers was then used for the deposition of the remains of the dead and at some point blocking stones were used to seal both the northwest and southwest chambers and the interior of the tomb was completely filled with a mix of chalk and sarsen rubble, earth, pottery sherds, items of flint and animal bone along with a small number of secondary burials.

The secondary phase of building then commenced around the entrance of the tomb with the addition of three huge sarsen blocking stones placed in a line to form a solid front across the facade and behind them a further pair of orthostats inserted to extend the line of the passageway to the very back of the central blocking stone. This whole area was then filled with sarsen boulders effectively sealing the tomb.

West Kennet was first investigated by John Thurnam who dug down into the western chamber in 1859 and recovered a quantity of human bone but it was not until 1955-6 that the interior of the tomb was fully excavated by Stuart Piggott after which fallen stones were re-erected and the eastern end of the barrow was reconstructed to its present form.

Within the chambers Piggott found the primary deposits consisted of the disarticulated skeletal remains of both males and females ranging from between 3-50 years of age although the majority were adult and most of these showed evidence of arthritis. Others showed signs of spina bifida, suggesting they belonged to a closely related family group. However many bones were missing and only a single skeleton was complete, that of an elderly man who is believed to have been one of the last burials within the tomb and may have been killed by the flint arrowhead found close to his throat. While the remains in the northeast and southeast chambers were mainly jumbled collections of bones those in the northwest and southwest chambers appeared to have been arranged by bone type and carefully tidied and placed against the back walls of the chambers.

For many years it has been believed that the total number of individuals represented by the bones in West Kennet was at least forty-six and that they had been interred over the course of around a thousand years before the tomb was then sealed and abandoned. This idea that Neolithic tombs remained open and had active lifespans of hundreds of years became the standard model for our understanding of their use and role in prehistoric society. However as more radio-carbon dates from the site have become available and particularly with the application of Bayesian statistical analysis to fine tune the results the story of the tomb has altered radically. A report in 2007 (Bayliss, Whittle, Wysocki) presented evidence that human remains were first placed in the tomb around 3650BC but that this primary phase, that involved the deposition of about thirty-six individuals, lasted for at most fifty years and more probably only half that time. There was then a period of inactivity within the chambers that lasted between 100 and 300 years before the process of filling the interior with chalk and rubble as well as the remains at least a further six bodies, mostly young children, began. It is this phase of activity that appears to have continued for around a thousand years before the erection of the blocking stones that finally put the tomb beyond further use.

View of West Kennet facade from the northeast.

View of the first phase entrance to West Kennet. The entrance capstone dominates the top of the picture while the two large upright sarsens and horizontal slabs of the facade are to the left and right of the image. The southeast and northeast chamber entrance stones are the pair of shorter uprights to the left and right of the puddle. The upright to the left bears the deep impressions from being used to sharpen stone or flint axes (known as a polissoir), presumably this was done while the slab was horizontal and before it was incorporated into the structure of the tomb, its position at the entrance may hold some symbolic meaning. Given what a tough stone sarsen is these grooves must represent countless hours of back-breaking work..

Plan of the interior of West Kennet. The original chambers, passageway and facade stones are shown shaded, the later blocking stones across the southwest and northwest chambers are shown as grey as are the final blocking slabs across the forecourt that sealed the tomb around 2300BC. The figures for the total burials in each chamber are taken from Bayliss, Whittle and Wysocki 2007.

A view of the interior of West Kennet during construction. The sarsen upright slabs that form the chambers, passageway and forecourt are in place as is the drystone course of limestone linking each slab at ground level. Further sarsen boulders have been used to pack the remaining space between the uprights and the chalk rubble that forms the body of the barrow itself has begun to be added around the chambers. From this point further slabs will be added to form a low corbelled roof over the chambers and passage topped with large slab capstones before more chalk rubble is added to create the final shape of the long barrow mound we see today.

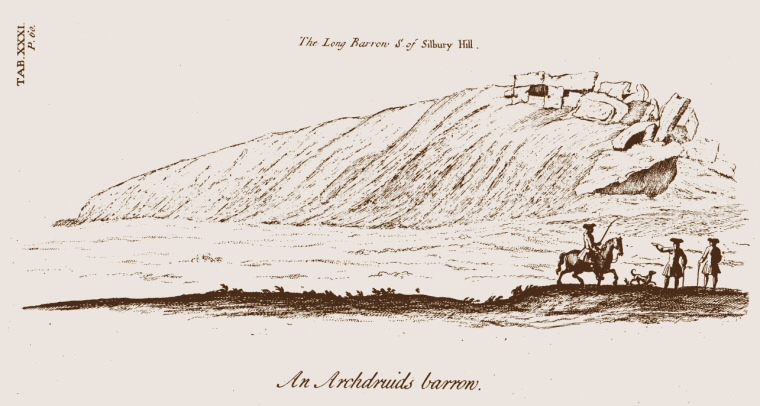

William Stukeley's drawing showing the ruinous state of West Kennet in the early 18th Century.

Site Visit / Photographs:

August 1997.

References:

Bayliss, A. Whittle, A. Wysocki, M. 2007. Talking About My Generation: the Date of the West Kennet Long Barrow. CAJ.

Burl, A. 1979. Prehistoric Avebury. London: Yale University Press.

Darvill, T. 2004. Long Barrows of the Cotswolds and surrounding areas. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Darvill, T. 2010. Prehistoric Britain. 2nd Edition. Abingdon: Routledge.

Joussaume, R. 1988. Dolmens For The Dead. Megalith Building throughout the World. Book Club Associates.

Lynch, F. 1997. Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications Ltd.

Malone, C. 1994. The Prehistoric Monuments of Avebury. London: English Heritage.

Stukeley, W. 1743. Abury, A Temple of the British Druids, with Some Others, Described. London: -