View looking southwest from Hordron Edge circle at sunset on the Winter Solstice 2009. |

||

A delightful if damaged stone

circle that stands close to Hordron Edge on a small triangular shelf of land known as Moscar

Moor at an altitude of about 330 metres above sea level. It has the imposing mass of Stanage Edge rising behind it to the east, a smaller stone circle and collection of cairns

and field systems on Bamford Moor a mile to the south and the carved

rock of Ladybower Tor to the west

on the opposite side of Ladybower Brook. It is believed to have been constructed during the early Bronze Age, probably around 2000 BC when populations in the Peak District were expanding into some upland areas as a result of a warming climate making what had been marginal land now viable for settlement, stock rearing and cultivation.  Although it is also known as the 'Seven Stones of Hordron' the circle currently consists of eleven stones while large gaps would suggest

that there were originally several more, possibly between sixteen

and twenty stones in total. Several other loose smaller stones

also lay around the circumference of the circle but these are unlikely

to be original and are more likely to have been placed there in recent

times by visitors in an effort to make the ring look more complete. Although it is also known as the 'Seven Stones of Hordron' the circle currently consists of eleven stones while large gaps would suggest

that there were originally several more, possibly between sixteen

and twenty stones in total. Several other loose smaller stones

also lay around the circumference of the circle but these are unlikely

to be original and are more likely to have been placed there in recent

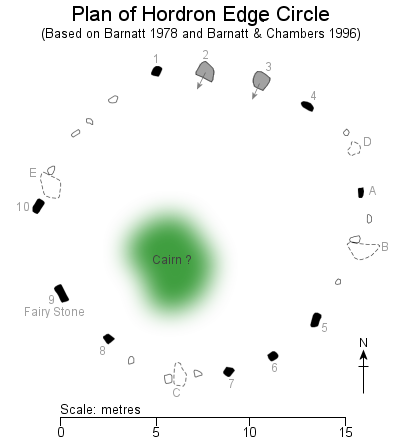

times by visitors in an effort to make the ring look more complete.Unlike many Derbyshire circles the stones are not set into the inner edge a bank but instead form a free-standing ring of between 15-16 metres diameter. They are all composed of the local gritstone and none are particularly large, ranging from about half a metre in height to just under a metre. Two of the stones along the northern arc are leaning inwards with Stone 2 (see plan left) now almost completely level with the the layer of peat that blankets this part of the moor. On the plan, standing stones are shown black, leaning stones grey, loose stones white and buried stones as dashed lines. The tallest and most prominent stone of the circle is located to the southwest of the ring (Stone 9 on the plan). This stone, which has become known as the 'Fairy Stone' (the stone to the right in the image above and separately below) could provide an intriguing insight into the world view and belief systems of the circle builders. When standing within the circle and looking outwards the top edge of the Fairy Stone bears a curious similarity in shape and angle to two distant hills seen on the horizon to the west-southwest. The first is the distinctive summit of Win Hill (known as Win Hill Pike) on the left 2 miles away and more particularly the distant but larger Lose Hill, 4 miles away to the right. This apparent mirroring of prominent landscape features by a distinctively shaped stone is also seen at the circle of Wet Withens a few miles to the south where the hill mirrored is Higger Tor over which the midsummer sun is seen to rise. However given that the Fairy Stone has stood on its exposed eminence for some 4000 years then we can't rule out the possibility that the particular shape it has today is no more than a fortuitous result of natural erosion. Peak Park archaeologist and author John Barnatt who has studied the sites of the area in great detail notes that at certain times of the year the setting sun can be seen to 'roll' down the slopes of Win Hill, these times being close to the Celtic festivals of Samhain and Imbolc and the traditional start of winter and spring respectively. These festivals may well have their origins in the early farming communities of prehistory when the marking of the passing seasons was vital for the prediction of the appropriate time to plant crops. Was the circle purposely sited at this location on Moscar Moor, close to Hordron Edge, to observe this phenomena and hence indicate the beginning of the agricultural year to the inhabitants of the moors? Was the shape of the Fairy Stone an attempt by the builders to draw the power of the sun or of two prominent landmarks, possibly sacred hills, into the circle or to acknowledge and venerate them? Or, are these theories just a result of our modern need to attribute meaning and symbolism where none was intended.  Whether

the mirroring and alignment were deliberate or just coincidental there is

no dispute that there are some impressive views westwards across the flooded valleys of the Rivers Derwent and Ashop

which

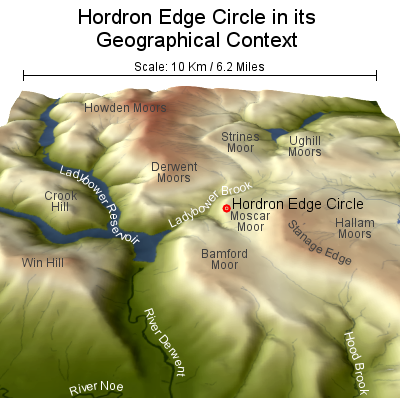

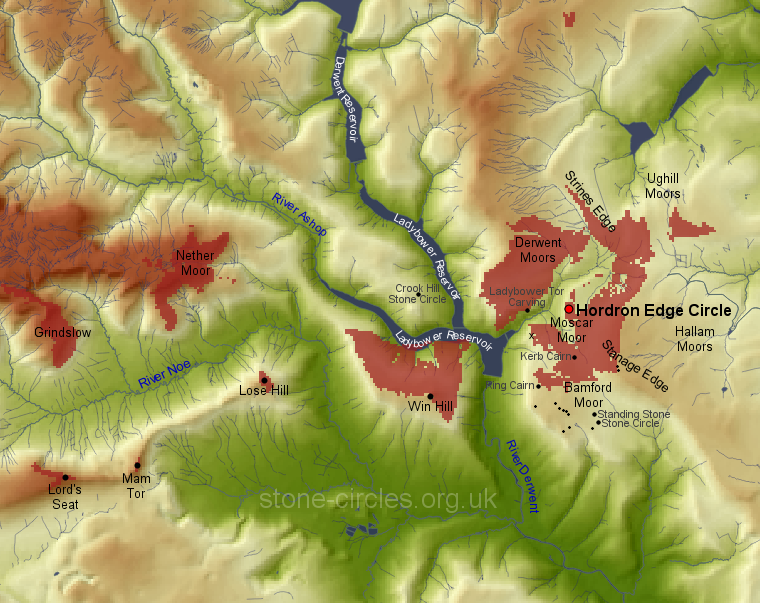

now hold the Ladybower Reservoir. The image left shows an elevated

view of an area of about 38 square miles (100 square kilometres) around Hordron Edge with the view looking north and shows the circle's relationship to the surrounding landscape features of this part of the Peak District. Whether

the mirroring and alignment were deliberate or just coincidental there is

no dispute that there are some impressive views westwards across the flooded valleys of the Rivers Derwent and Ashop

which

now hold the Ladybower Reservoir. The image left shows an elevated

view of an area of about 38 square miles (100 square kilometres) around Hordron Edge with the view looking north and shows the circle's relationship to the surrounding landscape features of this part of the Peak District.It must be noted however while the views on the ground seem extensive they are actually a collection of distinct 'windows' onto what are mostly local landscapes so the 360 degree vista from the circle is in fact quite restricted and large parts of the district are not visible (see viewshed analysis below). This was not a circle that was designed to stand out in its landscape, even today it retains a sense of seclusion, the sense of a place set apart. Bamford Moor, just on the other side of Jarvis Clough was the site of much activity during the period that the circle was built but its cultivated areas and the collections of cairns and other monuments don't seem to extend onto Moscar Moor or encroach upon the circle. Recent research. We know the circle has been somewhat tampered with as both antiquarian and modern records state that only nine or ten stones were contained within the ring. This was until somebody dug out a stone that was almost completely buried within a layer of peat on the north-eastern circumference of the circle and subsequently re-erected it (Stone A on the plan). This well-meaning but archaeologically damaging action lead John Barnatt to re-excavate the stone in 1992 to assess any potential damage done to the site, thankfully there was very little and the stone was then reset in its hole as a standing stone. The fact that the stone lay within the peat layer suggested that it had originally fallen or was taken down at least many hundreds of years ago before the peat formed although weathering along the edges and corners of the stone pointed to it having at least stood upright for some considerable amount of time. By probing the peat Barnatt was able to discover a further three fallen stones laying beneath the current ground surface, (Stones B, C and E) plus what may be the remains of a possible fourth, Stone D. Interestingly he could find no trace of buried stones along the northwest arc of the circle between Stone E and Stone 1. Was the ring left open at this point, was a complete circle re-modeled in prehistory or were the stones removed from the site in historic times as a convenient source a building material? A part of the site that was reassessed was a low rough hummocky area about 5.5-6 metres in diameter within the southwestern quadrant of the circle that had been largely overlooked (including by Barnatt 1978). This is now considered to be the remains of cairn but due to previous damage its purpose remains unknown. The antiquarian record. The first mention of a stone circle on Hordron Edge appears as early as the 16th century when it served as a boundary marker visited as part of a 'perambulation' of landowners and their tenants over the moors in what would seem to be a ceremony similar to a beating of the bounds. Joseph Hunter quotes from a record of the perambulation of 1574 as follows: 'a place where certeine stones are sett upon the ends and haveing markes upon them called the Seavenstones'. (Hunter 1819). The marks mentioned must be the weather-worn holes and grooves on the top of the stones while the spelling 'Seaven' is interesting, is this just an archaic spelling of seven or is it a personal name? Either way the single line gives us very little information about the site and we might hope that Derbyshire antiquarian Thomas Bateman might furnish us with more detail about the stones but sadly he only gives us only the most scant of descriptions, briefly noting that: 'on Hordron Edge, is another very complete cirque, composed of upright stones'. (Bateman 1848, p.115). He doesn't say how many stones were still present in the middle of the 19th century but 'very complete' implies that there were perhaps more stones than there are today. Towards the end of the century we at last start to get a little bit more detail about the circle. Sidney Oldall Addy records that: 'There are ten stones altogether, but only seven of them are standing upright.' (Addy 1893, p.55). He then adds the intriguing comment: 'It may be remarked that in the folk-lore of Hallamshire seven is still known as "the magical number."' (Addy 1893, p.58). He also provides us with our first illustration of the circle, painted by a Mr. Winterbottom -  The view appears to be looking roughly southwest over the circle and the Derwent Valley beyond, long before it was flooded by the reservoir. A few years later Ella Armitage paints a little more detail into our picture of the site: 'There is a well-preserved circle on Moscar Moor, near Hordron Edge, about a mile from the Sheffield Road. It consists of nine stones, some of which are rather more than 3 feet high. It differs from the circles spoken of previously in having no rampart; the stones rise out of the ground. It is about 16 yards in diameter.' (Armitage 1897, p.33). Armitage proves to be an astute observer, not only giving us dimensions but being the first to recognise that the circle is free-standing rather than being an embanked stone circle which is the more common form encountered in the Peak District. Viewshed analysis of Hordron Edge circle.  The image above shows a viewshed analysis of an area of about 15 km by 12 km (9.3 by 7.4 miles) or 180 square km (69 square miles) around the circle on Hordron Edge. The areas shaded salmon pink represent all the areas of land that can theoretically be seen by an observer standing at the circle given good viewing conditions. The observer would be impressed by the expansive 360 degree views but as can be seen above those actual views consist of a limited number of 'windows' most of which are no more than a few miles at most. The view east is totally dominated by the slopes of the looming Stanage Edge which blocks any vision of the Hallam Moors beyond in that direction. To the south short views across Moscar Moor then skim across Jarvis Clough to the rising slopes of the northern edge of Bamford Moor but apart from a large kerbed cairn the other ceremonial monuments of Bamford Moor (mostly cairns and marked as black dots above) remain out of sight. A Bronze Age field system and associated possible clearance cairns are just on the edge of visibility and marked above with a small 'x'. Continuing clockwise the view now jumps southwest across the valley of the River Derwent and the southern portion of the Ladybower Reservoir towards the long spine of Win Hill and the distinctive summit of Win Hill Pike which dominates the vision round to the west. Above this spine more distant glimpses of the tips of Lord's Seat, Mam Tor and Lose Hill float on the mid-distance horizon formed by Win Hill - depending on the weather of course, they can easily be lost on cloudy or misty days. As we continue round westwards the lower slopes of Win Hill are now blocked by Ladybower Tor and Ladybower Wood which juts into view as a distinctive local headland above which Grindlow and Nether Moor form the distant horizon. Located just on the opposite side of Ladybower Brook, Ladybower Tor and the southern slopes of the Derwent Moors now form an entirely local view back round towards the north blocking anything beyond which includes the damaged remains of the stone circle on Crook Hill. The remaining portion of our 360 degree view is taken up by Strines Edge and the southern slopes of the Ughill Moors to the northeast before Stanage Edge once again completes the circuit. To see what these views look like on the ground take a look at the 360 degree panorama further down the page. Additional notes. The name Hordron may possibly derive from 'white thorn', 'hor' being an old English word for white and 'dron' being a local dialect term for thorn, also seen in the name of the Derbyshire town of Dronfield (from Addy 1888). The two prominent landmarks seen from the circle, Win Hill and Lose Hill have a legend attached to them that claims their names derive from the result of a battle fought in the seventh century AD between the Anglian King of Northumbria and the Saxon King of Wessex. The soldiers of the Northumbrian army were camped the eastern hill with those of Wessex on the western hill, the battle being fought on the lower intervening land around the River Noe. The Northumbrians were ultimately the victors of the battle and the two hills were given their respective names as a memorial of each army's fate. Sadly there is no historical basis to the story, the name Win Hill may be a contraction of 'whin' meaning gorse or furze while author and musician Julian Cope suggests that Lose Hill may be a corruption of Lugh's Hill, Lugh or Lug being a character from Irish mythology. The 'Fairy Stone' has perhaps acquired its name more recently following reports of strange lights seen above the stone. If such a phenomena have occurred then disappointingly they are perhaps not fairies but more likely to be car headlights reflected from the reservoir surface and onto low clouds above the water. Either that or visitors seeing stars after the stiff hike up the hillside to reach the circle. Alexander Thom and his son Archibald surveyed the circle for their 1980 publication Megalithic Rings and designated the site as a 'Type A flattened circle', believing the circumference to be flattened inwards instead of being circular along the line of Stones 1, 2, 3 and 4. However, Barnatt's plan of 1996 on which the plan on this page is based shows that when the lean of Stones 2 and 3 is taken into account then Hordron Edge is in fact very close to being a true circle. There is a curious coincidence in the distances between the three sites of Hordron Edge circle and Win and Lose Hill. Measured from a 1:25000 OS map, the trig point on Win Hill Pike is 3.33km (just over 2 miles) from the stone circle, and the cairn and 'viewpoint' marker of Lose Hill is 3.38km away from Win Hill meaning the three locations are within 50m of forming an isosceles triangle ... on paper. In reality, the circle stands at an altitude of about 330m, Win Hill at 462m and Lose Hill at 476m, if anybody wants to work out the three dimensional trigonometry between the three and the corresponding straight-line distances, be my guest. In reality of course the true distance is that taken on foot by the prehistoric inhabitants of the land around the River Derwent and this is something that can no longer be recreated since the flooding of the valleys of the Derwent and Ashop to create Ladybower Reservoir in the 1930-40's. |

||

The Fairy Stone with Win Hill to the left, Lose Hill to the right.. |

||

Looking northeast across Hordron Edge Circle with Stanage Edge to the right. |

||

Night time HDR image of the Fairy Stone at Hordron Edge with the moon peeping from behind the clouds. |

||

|

Site Visits / Photographs: January 2008, November 2008, October 2009, December 2009 (2 visits), January 2010. References: Addy, S. O. 1888. A Glossary of Words used in the Neighbourhood of Sheffield. London: Trübner. Addy, S. O. 1893. The Hall of Waltheof ... Early condition and settlement of Hallamshire. Sheffield: Townsend. Armitage, E. 1897. A key to English Antiquities... Sheffield and Rotherham District. Sheffield: Townsend. Barnatt, J. 1978. Stone Circles of the Peak. London: Turnstone Books. Barnatt, J. 1987. The Design and Distribution of Stone Circles in Britain. Thesis, (PhD). University of Sheffield. Barnatt, J. 1986. Bronze Age Remains on the East Moors of the Peak District. D.A.J., Vol 106, 18-100. Barnatt, J. 1999. Taming the land: Peak District Farming and Ritual in the Bronze Age. DAJ, Vol 119, 19-78. Barnatt, J. 2000. ...Later Prehistoric Farming Communities...in the Peak. D.A.J., Vol 120, 1-86. Barnatt, J. and Chambers, F. 1996. Recent research at Peak District Stone Circles. D.A.J., Vol 116, 27-48. Bateman, T. 1848. Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire. London: John Russell Smith. Burl, A. 1995. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. London: Yale University Press. Cope, J. 1998. The Modern Antiquarian. A Pre-Millennial Odyssey through Megalithic Britain. London: Thorsons. Goddard, C. 2019. The South Yorkshire Moors. Hebden Bridge: Gritstone Publishing. Hunter, J. 1819. Hallamshire. The History and Topography of the Parish of Sheffield... London: Lackington. Merrill, J. 1992. Legends of Derbyshire. Matlock: Trail Crest Publications. Morgan, V. and Morgan, P. 2001. Rock around the Peak. Wilmslow: Sigma Leisure. Thom, A., Thom, A. S. and Burl, A. 1980. Megalithic Rings. BAR British Series 81. Oxford: BAR. Historic England Research Records Hob Uid: 312213. Scheduled Monument List Entry Number: 1018367. National Monuments Record Number: SK 28 NW 2. Scheduled Monument Legacy Number: 29823. County Number: DR 156. |

||