The Nine Ladies Stone Circle, Stanton Moor. View looking southeast.

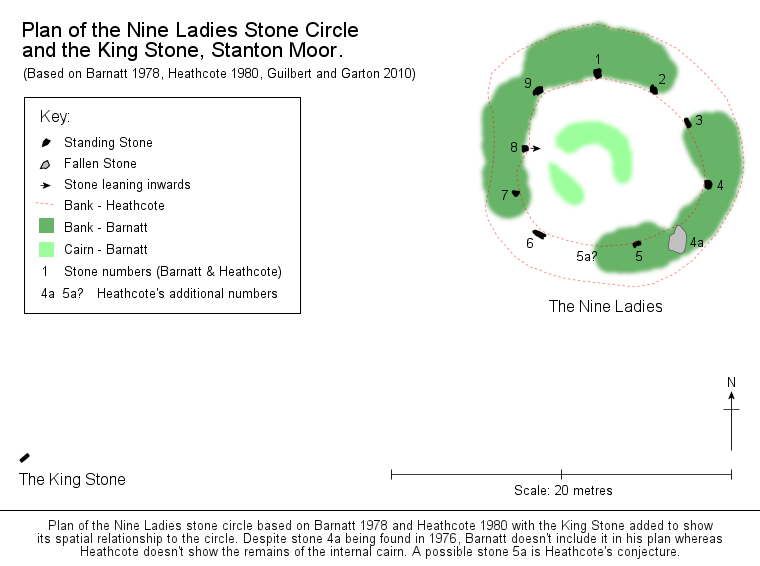

The stones of the circle are composed of the local Ashover Grit sandstone that was so attractive to the building and millstone industries that quarrymen gouged huge sections out of the western side of Stanton Moor between the mid 19th and mid 20th centuries. In keeping with many of the other stone circles located on the uplands of the East Moors in the Peak District none of the stones of the Nine Ladies are particularly tall, a couple reach about 90 cm while most of the rest are between 60-75 cm in height. Although they are thought to be unworked, being used as they were found by the builders of the circle, one stone (number 9 in the plan below) is a squat, flat topped block which appears to have been cut to shape, whether this was done when the circle was constructed or subsequently is not known. They are assumed to be in more-or-less their original positions although several of them lean, one particularly to the west (stone 8 on the plan) may have been disturbed and shifted inwards towards the centre of the circle.

The stones are laid out in a rather irregular ring of between 10.6 and 11.5 metres diameter and set into the inner face of an earth and rubble bank which would appear to make the Nine Ladies an embanked stone circle. The bank which passes unnoticed by many visitors has been badly damaged over the years and its original extent is not now clear but it probably extended a further 2-3 metres beyond the stones, while possible gaps towards the northeast and southwest (shown by Barnatt on the plan but not by Heathcote who shows a continuous ring) might hint at former entrances. Excavation of part of the bank in 2000 suggested the interior of the circle may have been slightly hollowed or 'dished' and perhaps scraped away externally so the appearance of a bank is actually the result of the interior of the circle being at a lower level than the surrounding landscape.

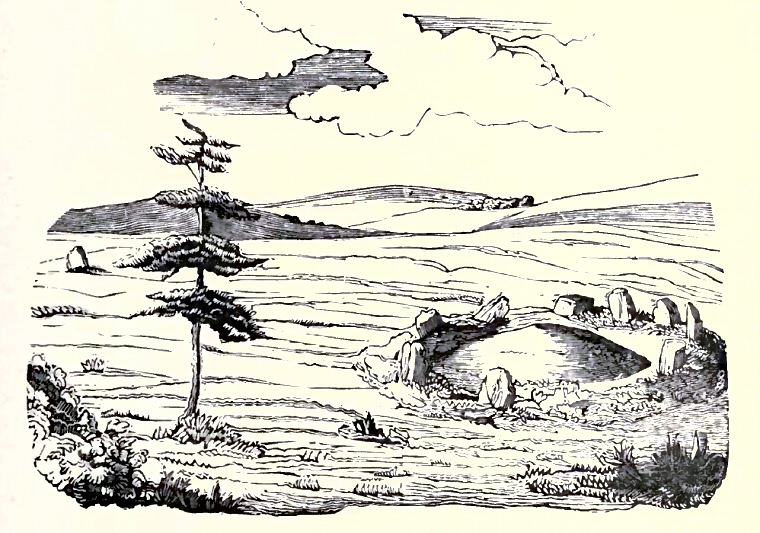

Within the circle and now almost totally destroyed are the low remains of an earth and rubble mound or cairn offset somewhat to the west of the centre and measuring about 5 metres in diameter. Whether this contained a burial or even held a standing stone is not known. The first known documentation of the Nine Ladies by Major Hayman Rooke in 1782 contained a rudimentary sketch showing the circle consisting of nine stones along with the outlying King Stone (image below). Rooke also shows something in the centre of the circle, this could either be the cairn or possibly a fallen stone within the ring, indeed on the subject of stones he says 'there appears to have been one in the centre'. Whether his drawing actually shows a stone or a cairn that he assumed a stone once stood on is not clear.

If a stone existed within the circle it had certainly gone by the time Thomas Bateman illustrated the site in the mid 19th century (image below). Bateman gives us a little more detail showing that the nine stones are set into a bank with a large mound in the interior and although his depiction of the site is perhaps a little fanciful with the surrounding landscape over dramatized, the layout of the stones would seem to tally with their current positions Strangely the illustration was shown flipped horizontally in his book 'Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire', perhaps a printing error by his publishers. The image below is shown in the correct orientation.

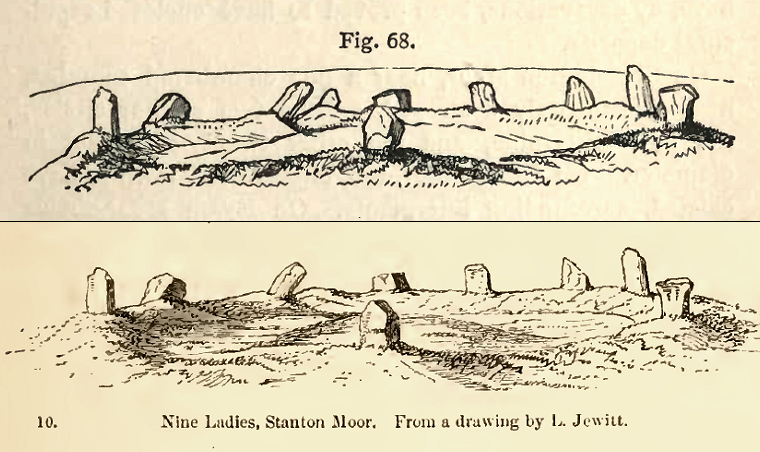

A more naturalistic sketch of the circle was provided by Llewellynn Jewitt in 1870 (also shown below) which also matches the current layout of the site except for a single mystery stone to the northwest of the circle, was this the stone that Rooke depicted that had since been removed from the centre and dumped on the edge of the ring? In his accompanying plan of the stones Jewitt only shows nine stones set into the bank so perhaps this extra stone was standing beyond the circle instead. As Jewitt lived within 2 miles (3 km) of the Nine Ladies and would have visited the moors often we would have to assume his plan and sketch were fairly accurate depictions of a site he was familiar with. Whatever the stone was must remain a mystery as two years later James Ferguson copies Jewitt's sketch but leaves this stone out although it's not clear whether he actually visited the circle and he perhaps thought it would confuse his readers if he showed a stone circle called 'Nine Ladies' with ten stones. Such are the vagaries of antiquarian accounts and illustrations.

About 34 metres to the west-southwest of the edge of the circle is

the 'King Stone', a single standing stone (image left) that was originally thought to be an outlier to the circle. Opinions changed in the mid 1980's when a survey found that it sat within a low damaged earthwork enclosure which lead to the belief that the stone may have formed part of a ring

cairn or even a remnant of a now destroyed stone circle. The 2000 investigation sought to shed more light on the enclosure but found however that the earthwork appeared to be modern, so the significance of the King Stone and its relationship to the Nine Ladies remains a mystery. It could indeed have been an outlying stone or perhaps formed part of a now destroyed avenue leading to the circle. The stone, which has a rectangular section of about 55 cm wide by 25 cm deep, once stood about 60 cm tall but sadly it was broken off near ground level in 1990 after being

hit by a careless vehicle driver. The top section lay propped against the base for several years until the two sections were reunited and repaired with steel pins and mortar ten years later in 2000. The resulting join is now hidden below the modern turf line giving the stone a rather squat boulder like appearance rather than the pillar it once was. The top section of the King Stone has graffiti on one face thought to date from the middle of the 19th century that reads 'Bill Stumps' together with a cross (or an elongated 'T') and the letter 'O'.

About 34 metres to the west-southwest of the edge of the circle is

the 'King Stone', a single standing stone (image left) that was originally thought to be an outlier to the circle. Opinions changed in the mid 1980's when a survey found that it sat within a low damaged earthwork enclosure which lead to the belief that the stone may have formed part of a ring

cairn or even a remnant of a now destroyed stone circle. The 2000 investigation sought to shed more light on the enclosure but found however that the earthwork appeared to be modern, so the significance of the King Stone and its relationship to the Nine Ladies remains a mystery. It could indeed have been an outlying stone or perhaps formed part of a now destroyed avenue leading to the circle. The stone, which has a rectangular section of about 55 cm wide by 25 cm deep, once stood about 60 cm tall but sadly it was broken off near ground level in 1990 after being

hit by a careless vehicle driver. The top section lay propped against the base for several years until the two sections were reunited and repaired with steel pins and mortar ten years later in 2000. The resulting join is now hidden below the modern turf line giving the stone a rather squat boulder like appearance rather than the pillar it once was. The top section of the King Stone has graffiti on one face thought to date from the middle of the 19th century that reads 'Bill Stumps' together with a cross (or an elongated 'T') and the letter 'O'.From 1877 the Nine Ladies and the King Stone were both enclosed within low stone walls to protect the stones and since the removal of these walls in 1985 the site has come under increasing pressure and ground surface wear caused by a rise in visitor numbers which eventually lead to a programme of conservation work in 2003. This included filling eroded areas with earth and re-turfing round the stones, in some old notes written after a visit to the site following this repair work I wrote-

'September 2003. The first thing I noticed when approaching the Nine Ladies was the pristine state of the turf and the tell-tale traces of the plastic netting beneath that peeps through in a couple of places. The neatness and tidiness of the grass gives the circle a bit of an artificial modern air but I can't really recall how the place looked when I was last here a few years ago. Once the wild grasses and flowers have started seeding themselves in the new turf the place will look a lot more natural. One thing to note though is that you'll be lucky to get the place to yourself as it is popular with families, couples and walkers at weekends, but I'll bet it's a cracking place first thing in the morning or in winter.'

There's a hint in there for anybody wishing to have peace and solitude at the site or to get photographs without the stones being obscured by other visitors. Although traces of camp fires, litter and modern graffiti scratched on the stones detracts from the site, the Nine Ladies potentially faced a bigger threat in the late 1990's when Stancliffe Stone proposed the re-opening of the Lees Cross and Endcliffe sandstone quarries close to the circle. According to the Stanton Moor Conservation Plan of 2007, an alarmed English Heritage -

'emphasised the national archaeological importance of this ‘very special landscape’, whose setting, atmosphere and amenity value would be severely harmed by the creation of an extensive industrialised landscape on the north-eastern edge of the moor, and by associated noise levels and traffic movements ... the proposed quarrying would have a significant impact, not only on the Nine Ladies stone circle and King Stone, but on the scheduled monument as a whole' (McGuire and Smith 2007).

As a result of the threat to the site a group of protesters established a camp close to the stones in 1999 and fought a long running battle to oppose the quarry proposals and to keep the plight of Stanton Moor in the public eye, finally being vindicated in 2008 when Stancliffe Stone relinquished all future mining rights at the two quarries.

The Nine Ladies are located towards the northeast of Stanton Moor at a height of about 298 metres above sea level and form part of a chain of circles and ring cairns that runs in a rough line just to the east of the spine of the moor including the badly damaged circle of Stanton Moor I 200 metres to the north, Stanton Moor III which is either another circle or ring cairn and the similar circle of Stanton Moor IV, 240 metres and 630 metres to the south-southwest respectively. This eastern side of the moor is rich in prehistoric monuments (see Stanton Moor Introduction page for overview maps), many others probably existed to the west but have subsequently been destroyed by mining operations and although there have been finds from some of the nearby barrows and cairns nothing has been found from within the stone circle itself that would allow it to be precisely dated. Assuming it is contemporary with the collection of collared urns, pygmy cups, barbed and tanged arrowheads and flint, bone and occasionally bronze tools recovered from the moor then the circle probably dates from the early Bronze Age, perhaps sometime between 2000-1500BC.

The reason why this precise spot was chosen is not clear, there are no obvious landscape features that the circle might reference such as the possible relationship between the Nine Stone Close circle and the rock outcrop of Robin Hood's Stride both about a mile and a half away to the southwest, while a slight rise in the land to the north and west would seem to block any views out in those directions.

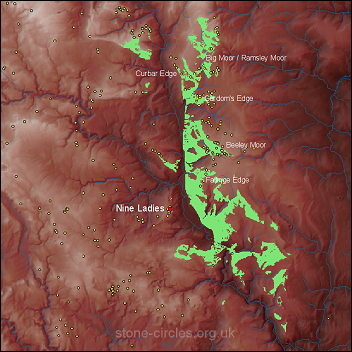

However as the viewshed analysis left shows (click to enlarge) there are sweeping views eastwards towards areas of high ground on the other side of the River Derwent. These include several concentrations of Bronze Age monuments particularly those on Big Moor, Curbar Edge, Gardom's Edge, Beeley Moor and Fallinge Edge, although we have no way of knowing whether the intervisibility the analysis suggests was an important factor to the builders of the circle. John Barnatt from the Peak District Archaeology Service sees these small stone circles as essentially local monuments, each constructed to serve the needs of their own local community. As such perhaps the views from the circle were never important and the stones were erected instead to monumentalise or commemorate a pre-existing barrow or cairn or to serve as a ritual and ceremonial centre for the population of Stanton Moor, the focus perhaps being inwards rather than outwards.

The reason why this precise spot was chosen is not clear, there are no obvious landscape features that the circle might reference such as the possible relationship between the Nine Stone Close circle and the rock outcrop of Robin Hood's Stride both about a mile and a half away to the southwest, while a slight rise in the land to the north and west would seem to block any views out in those directions.

However as the viewshed analysis left shows (click to enlarge) there are sweeping views eastwards towards areas of high ground on the other side of the River Derwent. These include several concentrations of Bronze Age monuments particularly those on Big Moor, Curbar Edge, Gardom's Edge, Beeley Moor and Fallinge Edge, although we have no way of knowing whether the intervisibility the analysis suggests was an important factor to the builders of the circle. John Barnatt from the Peak District Archaeology Service sees these small stone circles as essentially local monuments, each constructed to serve the needs of their own local community. As such perhaps the views from the circle were never important and the stones were erected instead to monumentalise or commemorate a pre-existing barrow or cairn or to serve as a ritual and ceremonial centre for the population of Stanton Moor, the focus perhaps being inwards rather than outwards. The name Nine Ladies probably relates to the belief that the stones were girls turned to stone for dancing on the Sabbath, the King Stone under its alternate guise of 'The Fiddler' being a musician similarly petrified for providing the music for the illicit dancing.

See also the nearby Doll Tor stone circle on the south-western edge of the moor.

The view looking southwest over the Nine Ladies circle.

A rather simplistic drawing of the Nine Ladies and the King Stone by Hayman Rooke 1782 looking roughly north. Rooke doesn't show much detail of the site, he doesn't include the bank that the stones sit in but draws something in the centre of the circle, this could be either a small cairn or possibly even a fallen stone.

Illustration by Thomas Bateman looking roughly northwest showing the Nine Ladies circle set within an embankment and with a sizable mound towards its centre, the King Stone is shown to the upper left. The drawing seems to be taken from an unpublished watercolour by Bateman that is now in the possession of Sheffield City Museum but was shown as a mirror image in his book 'Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire' published in 1848 (Guilbert and Garton 2010). It is shown here flipped to the correct orientation.

Two very similar illustrations of the Nine Ladies, the upper one by local antiquarian Llewellynn Jewitt 1870, the lower by James Ferguson 1872 but copied from Jewitt. Both give a better impression of how the circle once looked with a nicely drawn embankment and low mound in the centre, however Ferguson shrinks the mound and also omits a mysterious tenth stone that Jewitt shows beneath the text 'Fig 68.' which perhaps goes to show we can't always rely on antiquarian sketches. The views are looking almost due north.

Site Visits / Photographs:

1992, September 2003 (two visits).

References:

Andrew, W. 1907. Prehistoric Stone Circles of Derbyshire. In Cox, C. (ed.) Memorials of Old Derbyshire. 70-88.

Barnatt, J. 1978. Stone Circles of the Peak. London: Turnstone Books.

Barnatt, J. 1986. Bronze Age remains on the East Moors of the Peak District. D.A.J., Vol 106, 18-100.

Barnatt, J. 1987. The Design and Distribution of Stone Circles in Britain... Thesis, (PhD). University of Sheffield.

Barnatt, J. 1999. Taming the land: Peak District farming and ritual in the Bronze Age. D.A.J., Vol 119, 19-78.

Barnatt, J. and Chambers, F. M. 1996. Recent research at Peak District Stone Circles. D.A.J., Vol 116, 27-48.

Bateman, T. 1848. Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire. London: John Russell Smith.

Burl, A. 1976. The Stone Circles of the British Isles. London: Yale University Press.

Burl, A. 1995. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. London: Yale University Press.

Burnham, A. (Ed.). 2018. The Old Stones. Field Guide...Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland. London: Watkins.

Cope, J. 1998. The Modern Antiquarian. A Pre-Millennial Odyssey through Megalithic Britain. London: Thorsons.

Edmunds, M. and Seaborne, T. 2001. Prehistory in the Peak. Stroud: Tempus.

Ferguson, J. 1872. Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries; their age and uses. London: Murray.

Guilbert, G. 2001. 'Foolishly inscribed' but well connected - Graffiti on the King Stone. D.A.J., Vol 121, 190-195.

Guilbert, G. 2005. King graffiti sequel - The case against 'Flint Jack'. D.A.J., Vol. 125, 95-99.

Guilbert, G. and Garton, D. 2010. Nine Ladies...exploratory excavations...1988-2000. D.A.J., Vol. 130, 1-62..

Heathcote, J. P. 1980. The Nine Ladies Stone Circle. Derbyshire Archaeological Journal, Vol. 100, 15-16.

Jewitt, L. 1870. Grave-mounds and their Contents: A Manual of Archaeology. London: Groombridge.

Matlock Mercury. 2007. Quarry fight is over. Matlock Mercury. 15 June.

McGuire, S. and Smith, K. 2007. Stanton Moor Conservation Plan 2007. Peak District National Park Authority.

Morgan, V. and Morgan, P. 2001. Rock around the Peak. Wilmslow: Sigma Leisure.

Pegge, S. 1787. Observations... on the Stanton Moor... Druidical Temple. Archaeologia, 8, 58-62

Rooke, H. 1782. An account of some Druidical Remains on Stanton and Hartle Moor. Archaeologia, 6, 110-115.

Historic England Research Records Hob Uid: 311392.

Scheduled Monument: 1009300.

HER Number: 12908.

County Number DR 4.